The Evolutionary Psychology of Meaning in Life

The Subjective Sense of Meaning as Indicator of Psychological Integration

If modern evolutionary psychology is any indication, all the philosophers, psychologists, and psychiatrists who have discussed the centrality of meaning to the human experience—including Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl, Carl Jung, Abraham Maslow, and more recently John Vervaeke and Jordan Peterson—must all be very misguided. Meaning, after all, doesn’t get us sex, resources, or status. It doesn’t directly contribute to our inclusive fitness, so what good is it?

The evolutionary psychologist David Pinsof had a nice discussion about this a while back in a Substack post that was appropriately titled “The Meaning of Life is Bullshit”. In that post he articulated the question like this:

Some people gaze up at the stars and wonder what it’s all about. Me, I gaze up at the stars and wonder why people wonder what it’s all about. Why do people do this?

It’s not at all obvious. We’re animals—specifically, apes—and pondering the meaning of life is a strange thing for an ape to do. It doesn’t get us food or sex. It doesn’t keep us safe from predators. It captures our limited attention without providing any obvious, Darwinian payoff. So maybe the real mystery isn’t the meaning of life, but why apes like us care about the meaning of life.

It’s a good question. Pinsof argued in that short post that people—mostly intellectuals—talk about the meaning of life as a way of justifying themselves to other people. To put it succinctly, he thinks that:

They’re looking for a way to rationalize their lives—to dress up their careers and political loyalties in self-important verbiage. They’re looking for a not-too-obviously-false story they can tell about themselves to look morally and intellectually sophisticated, so that other nerds will praise them as “profound,” “revolutionary,” and “humane.” Debates about the meaning of life are ultimately a convoluted form of status jockeying.

This is a plausible hypothesis, and I’m sure there is some truth to it. But it will have little to do with my theory in this article. In the first place, the question itself, “What is the meaning of life?” is basically a red herring. I can’t think of a single sophisticated thinker on the topic who has framed the question like this. Despite the tropes, people are not usually concerned with the meaning of life (as if there were a single answer that applied for everyone). Rather, we are concerned with living meaningful lives. We are concerned meaning in life, the sense that our lives are worthwhile, that we matter, that we are contributing to something larger than ourselves.

And contra Pinsof, it is far from being only intellectuals who care about leading meaningful lives. If anything, the opposite is true. It is mostly intellectuals who tend to think of meaning as something secondary or epiphenomenal. No shade to Pinsof, but he—like every other evolutionary psychologist I’ve seen broach this topic—appears to be unacquainted with the empirical research literature on the causes and consequences of meaning in life that has been compiled over the last 30 years or so (see King & Hicks, 2021 for a relatively recent review). That research has revealed that not only is the sense of meaning in life commonplace, it is correlated with pretty much everything we care about: mental health, positive affect, life satisfaction, etc. These are correlations, of course, and I don’t mean to imply that meaning in life causes these outcomes. I only mean to imply that the subjective sense of meaning is part of the network of variables that indicate a life well-lived. It actually matters to most of us that our lives are meaningful. As the authors of the review I just cited concluded:

The commonplace nature of meaning in life and its strong relationship to positive affect may surprise psychologists, but many of the conclusions that science offers about meaning in life are likely neither counterintuitive nor surprising to most anyone else. Everyday people appear to be living lives of meaning despite the best efforts of academic psychologists and philosophers to persuade them that meaning in life is rare or that there is, in fact, no meaning in life. (p. 578)

Contra Pinsof, my sense is that it is psychologists and intellectuals who continually act surprised about (or deny) the centrality of meaning, not regular people, for whom it seems relatively obvious. Why do you think people like Jordan Peterson (Maps of Meaning) and John Vervaeke (Awakening From the Meaning Crisis) became so wildly popular on the internet? Why is Nietzsche such a popular philosopher among non-academics and non-philosophers? Why did Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search for Meaning sell more than 16 million copies? Is it primarily intellectuals, cloistered within the status games of academia, who are attracted to what these figures have to say? Please.

As it stands, evolutionary psychology seems to have no way to integrate the empirical literature on meaning in life into its current concepts and frameworks. In fact, a 2022 book on “Positive Evolutionary Psychology” totally left out any discussion of meaning, a glaring oversight that was pointed out by Scott Barry Kaufman in the foreword to the book. As Kaufman noted:

Geher and Wedberg cover a wide gamut of topics in this book, ranging from cooperation, to kindness, to religion, to happiness, to gratitude, to resilience. These are indeed topics that are being investigated in positive psychology. However, one topic is notably absent from this list: meaning. (p. ix)

Kaufman spends much of the foreword talking about why this is such a glaring oversight. Meaning is central to the human experience, and evolutionary psychologists seem to have little idea of what it is or what to do with it. Trying to explain meaning in life as a byproduct of other more evolutionarily obvious motivations like status-seeking (as Pinsof implies) may capture part of the picture, but we will see that it clearly fails to explain the full range of phenomena associated with meaning in life. Other evolutionary psychologists, like Geher and Wedberg, have simply ignored the topic altogether, likely because they have no theoretical framework within which they could discuss the research.

One might think that I’m being overly critical of evolutionary psychology here. But the fact is that evolutionary psychology was my first love, intellectually speaking, and the first academic literature I ever did a real deep-dive into. Cosmides & Tooby, David Buss, Martin Daly, and so on are all intellectual heroes of mine. Evolutionary psychology’s inattention to meaning in life is not indicative of a failure for the field as a whole, and this post is not meant to detract from the overall project of evolutionary psychology. Far from it. To the contrary, I will be using the concepts and tools of evolutionary psychology to understand the evolved function of the subjective sense of meaning in life.

I think there is a relatively straightforward evolutionary explanation for the subjective sense of meaning in life that is supported by multiple lines of research from independent research literatures. To put it succinctly: the subjective sense of meaning in life is the output of an internal regulatory variable tracking the degree of psychological integration, or lack of conflict, between psychological adaptations in addition to the values, beliefs, goals, and perceptions that facilitate the pursuit of adaptive outcomes. In other words, people who feel as if their lives are meaningful are people whose values, goals, beliefs, behaviors, and perceptions are functionally integrated such that there is little conflict or contradiction between them.

Evolutionary psychological explanations pose both an adaptive problem and an evolved solution to that problem, which is a psychological adaptation. There is an adaptive problem, which is that pursuing multiple semi-autonomous adaptive goals at the same time in a world of near-infinite complexity is extremely difficult from a computational perspective. Part of the adaptive solution to this problem is the existence of an internal regulatory variable which tracks conflict between sub-systems. This internal regulatory variable produces the feeling of anxiety, on the one hand, when there is too much internal contradiction, and meaning, on the other hand, when everything is well-integrated. As we will see later on, anxiety and meaning are negatively correlated, but the search for meaning is positively correlated with anxiety. Both of these findings support the idea that they are outputs of the same underlying psychological adaptation.

In order to unpack this theory I will first need to do two things. We will need to review the basic structure of the mind according to evolutionary psychology, including the concepts of psychological adaptation, massive modularity, and internal regulatory variables. Next, we will need to introduce Hirsh, Mar, & Peterson’s 2012 psychological entropy framework, derived from cybernetics, which will help us to understand why psychological integration is such an important and difficult problem.

After these theoretical frameworks are in place, we will review the empirical evidence supporting the idea that meaning in life is a function of psychological integration. This includes the large social & personality psychology literature on meaning in life in addition to research on meaningful experiences like the psychedelic experience. We will also review evidence that there are pathological or anti-social ways of achieving both meaning and psychological integration, including clinical delusions and extremist political and religious ideologies.

When I was still in academia I had plans to publish something like this as a journal article. Since I’m not doing that anymore, I can write like a normal person (instead of writing like an academic), and include some stuff that I think is important but would never get published in mainstream journals—not for lack of evidence, but mostly due to the biases of academics. And I get to publish this instantly instead of waiting nine months for reviewer 2 to get his shit together. So it’s probably better this way. Still, if you’re an academic reading this who steals my ideas without attribution, I will find you, and I will destroy you.1

Some Basics of Evolutionary Psychology

I will avoid discussion of the theoretical commitments of evolutionary psychology and instead focus on the basic aspects of the field that will be necessary for understanding the theory of meaning in life I will put forward here. These are: 1) psychological adaptations as domain-specific solutions to recurrent adaptive problems, 2) massive modularity as the idea that the mind is made up of a collection of semi-autonomous psychological adaptations, and 3) internal regulatory variables as summary magnitudes that track evolutionarily relevant internal states in order to affect behavior based on those states.

I am assuming, for the sake of brevity, that my audience both believes in and has some basic understanding of Darwinian evolution, in addition to the modern synthesis of evolution and genetics. I also won’t be addressing the beefs I have with evolutionary psychology’s bad cognitive science, since it’s not really relevant to what I’m doing here. Suffice it to say, the mind is not best thought of as “computational” in the way that evolutionary psychologists tend to think it is, though acting as if the mind is computational in this way can still lead to useful and interesting research.2

Psychological Adaptations

The concept of “adaptation” is easy enough to understand. An adaptation is an evolved solution to a recurrent evolutionary problem. The heart, lungs, brain, kidneys, and so on are all adaptations. They solve problems that organisms in our lineage have faced for millions of years. We need a continual supply of oxygen to support ATP (i.e., energy) production? The lungs and circulatory system are adaptive solutions to that problem. We need to filter out toxins from our food, drink, and blood? The kidneys are an adaptive solution to that problem. We need to reproduce? We’ll probably need some adaptive equipment for that. We need to integrate sensory information so as to act appropriately in the face of novel circumstances? Brains are pretty good adaptations for that. And so on.

Psychological adaptations are like that, but instead of being physical organs they exist in the mind. Evolutionary psychologists believe, as most of us do, that the mind is dependent on the brain, but psychological adaptations (or “modules”) do not have a strict location in the brain. There is nowhere in the brain you could point to and say “there is the psychological adaptation for status-seeking” or anything like that. Rather, we must make inferences about the existence and structure of psychological adaptations on the basis of behavior. Psychologists already make these kinds of inferences, but they typically do so with no reference to evolutionary theory or adaptive function. Hence the necessity of evolutionary psychology.

Psychological adaptations are considered to be universal, domain-specific, and reliably developing. Their universality is due to the fact that all human beings, regardless of race or culture, only split off from a primary lineage about 50,000 years ago, which is long enough to produce some differences, but not long enough to evolve new complex psychological adaptations. Complex adaptations usually take millions of years to evolve, so all complex psychological adaptations are shared among humans everywhere.

Psychological adaptations are domain-specific in the sense that they typically deal with a relatively narrow class of input. The “cheater-detection” module that was famously proposed by Leda Cosmides in the 1980s deals with sensory input indicating that someone is trying to violate a social contract. The snake-detection module is present in many primates, and allows us to detect and respond to snakes with little-to-no training, given that venomous snakes have been a common source of injury and death for primates in our lineage for 10s of millions of years. Evolutionary psychologists have produced empirical evidence supporting the existence of domain-specific psychological adaptations for a number of other adaptive problems, including gains or losses in social status (pride and shame, respectively), mate acquisition and retention, parenting, disease avoidance, coalition-building, leadership & following, among others.

Psychological adaptations are reliably developing in the sense that they reliably come online at certain points in development given that someone is developing within an environment that is close enough to the one in which the adaptation evolved. For example, someone might not develop language properly if they are brutally neglected as a child, kept from interacting with other human beings, and therefore fail to develop the language skills that most children develop as a matter of course. But this doesn’t mean that language isn’t “innate” as evolutionary psychologists use the term. Similarly, sexual attraction doesn’t develop normally in castrati, but that doesn’t mean sexual attraction isn’t innate. Under normal conditions, language and other psychological adaptations reliably develop and are therefore considered innate in the sense we care about.

Regardless of my differences with evolutionary psychology’s cognitive scientific framework (i.e., the input—>computation—>output model of how the mind works), the basic insight that the mind contains many reliably developing domain-specific psychological adaptations strikes me as obviously true, and is supported by a wealth of empirical evidence. This leads to the next topic, which is the massive modularity thesis.

Massive Modularity

The topic of modularity, as that term is used by evolutionary psychologists, is so often misunderstood by non-evolutionary psychologists that some evolutionary psychologists have argued that we should just stop talking about it, or call it something else. The confusion around the topic was nicely articulated by Piatraszewski and Wertz in their 2021 paper “Why Evolutionary Psychology Should Abandon Modularity”. To be sure, these authors don’t actually think evolutionary psychology should abandon thinking about the mind as modular. They are just as confident as I am that the mind contains many domain-specific psychological adaptations. Rather, they want evolutionary psychologists to start using different language to discuss this fact since the word “modularity” consistently generates so much confusion.

Understanding why the term “modularity” generates so much confusion is actually a good way to introduce what evolutionary psychologists mean by massive modularity. In order to understand why massive modularity is so often misunderstood, we must understand that evolutionary psychologists are trying to explain the mind at a different level of analysis than most other psychologists. Evolutionary psychologists are concerned with ultimate rather than proximate reasons for behavior, and this difference generates no shortage of confusion among psychologists who are used to thinking about behavior only from the proximate perspective.

Let me give a simple example to demonstrate the difference. We want to understand why someone can’t stop eating chocolate cake. They are eating themselves to death and we want to know why. At the proximate level of analysis, the person can’t stop eating cake because it tastes good and it makes them feel good. They derive pleasure from eating cake, and they are in pain when they can’t eat cake. The fact that they are seeking pleasure and avoiding pain provides a proximate explanation for their cake-obsession.

But the ultimate level of analysis asks why cake is pleasurable in the first place. This requires an adaptive, evolutionary explanation. Cake is pleasurable because calories were rare and precious throughout most of our evolutionary history (at least compared to our modern state of abundance), and so we evolved psychological adaptations for craving sugary, fatty, calorie-dense foods. The ultimate explanation posits an adaptive problem and an adaptive solution: calorie shortages are the problem, taste receptors and cravings for sugary, fatty foods are the solution.

Ultimate explanations are typically referred to as the functional level of analysis, consisting of some evolutionary explanation while proximate explanations within psychology typically occur at the intentional level of analysis, consisting of beliefs, goals, desires, feelings, etc., which proximately lead to the commission of some behavior.

Functional explanations need not conflict with explanations at the intentional level of analysis. It is equally true that the cake-obsessed man from our previous example eats too much cake because it is pleasurable (the intentional level of analysis) and because cake-eating is the product of evolved psychological adaptations being inappropriately applied to a novel, calorie-rich environment (the functional level of analysis). Intentional and functional explanations are not contradictory, but complementary, at least in principle.

Unlike some cognitive scientists before them (e.g., Jerry Fodor), evolutionary psychologists believe the mind is functionally modular, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that the mind is intentionally modular too. And herein lies the confusion. Psychologists who are used to thinking at the intentional level of analysis have proven themselves time and again to be unable or unwilling to think about modularity at the functional level of analysis, and therefore constantly accuse evolutionary psychologists of positions that they do not hold. Piatraszewski and Wertz (2021) comment that:

This confusion of levels of analysis—what we call the modularity mistake—unleashed a cascade of profound misunderstandings that has wreaked havoc for decades. It has led to a perverse view of what evolutionary psychology is and what it is trying to do and, even more broadly, a perverse view of what is entailed by claims (coming from any theoretical perspective) that something is a function or a mechanism within the mind. (pp. 469-470)

All that modularity means for evolutionary psychologists is that “mental phenomena arise from the operation of multiple distinct processes rather than a single undifferentiated one” (Barrett & Kurzban, 2006 p. 628) and that these distinct processes were shaped by our evolutionary history to solve recurrently adaptive problems.

There are some things I disagree with evolutionary psychologists about when it comes to how modules actually work. At the very least, I would frame things differently than mainstream evolutionary psychologists do. Evolutionary psychologists tend to understand modules as input-output devices. Modules take in some sensory input, perform some computations, then spit out behaviors as an output. This model is fine for some purposes, but it downplays the fact that many of our psychological adaptations are extremely proactive, in addition to being semi-autonomous, meaning that a psychological adaptation acts as if it has its own autonomous goals, and pursues those goals even at the expense of other psychological adaptations or the organism as a whole.

For example, we clearly have psychological adaptations that compel us to pursue food and sex. These adaptations are proactive. They don’t simply take in input and spit out behavior. They are constantly and proactively compelling the organism to engage in behavior that will culminate in achieving the goals of attaining food or having an orgasm. These adaptations are semi-autonomous because they pursue their goals in a way that doesn’t necessarily take into account the organism as a whole. In pathological cases, these goals will be pursued even at the expense of the whole organism. For example, some people literally eat themselves to death, and some people ruin their entire lives over the pursuit of sex. Other motivational systems are the same. Each “wants” to dominate the psyche, and the strongest among them can become the dominating factor in a person’s life if left unchecked. Workaholism, attention-seeking, and people-pleasing tendencies are other examples of psychological adaptations that can dominate the psyche at the expense of the whole organism.

Their semi-autonomous nature means that psychological adaptations will often conflict with each other in pursuit of their adaptive goals. For example, I may want to lose weight, and this desire may be influenced by psychological adaptations associated with status-seeking or mate acquisition and retainment. On the other hand, I may really want to eat the delicious chocolate cake sitting on my kitchen counter. I may struggle internally as I stare longingly at the cake in all its chocolatey goodness, then feel guilty as I stuff my face, knowing that I had already committed to avoiding sugary foods. Faced with such an internal conflict, some people will even go so far as to lock their own refrigerators at night to avoid breaking their diets.

The same is true of the man who loves his wife and children, wants to keep them around, doesn’t want to hurt them, and is yet tempted by an attractive new co-worker. Parental and mate retention adaptations here come into conflict with sexual and mate acquisition adaptations. Behaviorally, the man might end up controlling himself and maintaining his family, or he could give in and hurt the people he loves. The conflict could turn out either way, but the internal struggle in making the decision is very real. Different parts of us compete for dominance within us, and we feel this conflict in the form of anxiety, uncertainty, guilt, and so on.

There are multiple ways we may respond to these internal conflicts. Some people end up engaging in a kind of internal tyranny. They can’t do anything in moderation, so they become rigidly attached to a diet, to celibacy, to abstinence of one form or another. They become ascetics out of necessity. On the other hand, some people become characterized by a kind of internal anarchy. They are impulsive, leaping from one desire to the next, eating and sexing up anything and anyone who draws their attention. We often consider these people addicts, even if it’s not a drug they are addicted to.

And there are some people who seem capable of moderation and restraint without becoming sticks in the mud. They somehow manage to be disciplined enough to maintain their major life projects, and spontaneous enough to have a good time when the opportunity arises. These people appear to have found some internal harmony and integration.

In fact, the problem of integrating our psychological adaptations such that there is little conflict between them, and such that none can dominate the psyche at the expense of the whole, is incredibly difficult from a computational perspective. Given that all of our values, goals, and beliefs are ultimately the product of some psychological adaptation or another, it would be better (all else being equal) if they are all integrated with each other such that there is little conflict or contradiction between them. My thesis here will be that the subjective sense of meaning is part of a package of psychological adaptations that helps us to solve this problem of integration.

Meaning in Life as Mood, Not Emotion

In principle, evolutionary psychologists understand the problem of integration and coordination that arises from having multiple competing psychological adaptations, and have put forward some ideas about how it is solved. In a 2008 chapter, Tooby & Cosmides discuss emotions as evolved adaptations for coordinating behavior in this way. Emotions coordinate the action of multiple underlying adaptations to avoid conflicting behaviors. For example, the emotion of fear shifts perception and attention such that ordinary noises (e.g., the creaking of the stairs, rustling in the bushes) are attended to that would normally be ignored, raises the heart rate to prepare for fight or flight, activates sweat glands, shuts off some digestive and reproductive functions, and so on. Fear coordinates the mind and body to optimally respond to some threat.

But the subjective sense of meaning in life is clearly not an emotion like fear, anger, or disgust. These emotional states coordinate behavior over relatively short periods of time, while meaning in life is a state of mind that appears to affect behavior over much longer periods of time. In a 2021 chapter, Marco Del Giudice put forward a framework for understanding how adaptive goals are coordinated over longer periods of time. He suggests that moods are third-order coordination programs that constrain and coordinate behavior in a more diffuse and long-term way than emotions do:

The concept of higher-order coordination problems shines new light on the old and perplexing question of what differentiates emotions from moods. Phenomenologically, moods are long-lasting and have a diffuse rather than focused quality; unlike emotions, they do not have a specific cause or triggering object, and do not prompt specific behaviors or action tendencies. At the same time, they have a powerful (if non-specific) impact on motivation, and dispose people to appraise new situations in affect-congruent ways (e.g., attributing hostile intentions to others when one is in an irritable mood). (p. 20)

Meaning in life, as it is measured by social and personality psychologists, is clearly a mood rather than an emotion. It is understood not as a fleeting feeling, but as something that characterizes a person’s experience over long periods of time. Furthermore, meaning in life can have a powerful impact on motivation, as people who feel an acute lack of meaning in life seek out meaning in a variety of ways.

In sum, while emotions can coordinate the actions of multiple psychological and physiological adaptations over short periods of time, they cannot do so over longer periods of time. While some experiences may be felt as meaningful or not, meaning in life is typically understood as a state of mind that occurs over long periods of time, and is therefore best understood as a mood rather than an emotion.

Internal Regulatory Variables

In order for the subjective sense of meaning to play this integrative role, it must be the output of what evolutionary psychologists call an internal regulatory variable. Tooby & Cosmides (2008) state that:

We expect that the architecture of the human mind, by design, is full of registers for evolved variables whose function is to store summary magnitudes that are useful for regulating behavior and making inferences involving valuation. These are not explicit concepts, representations, goal states, beliefs, or desires, but rather indices that acquire their meaning via the evolved behavior-controlling and computation-controlling procedures that access them. That is, each has a location embedded in the input–output relations of our evolved programs, and their function inheres in the role they play in the decision flow of these the programs. (p. 130)

My contention is that there is some internal regulatory variable which tracks conflict and contradiction between other sub-systems. This can include conflict between goals, beliefs, values, and so on. This internal regulatory variable would feed into psychological mechanisms which produce anxiety, and it’s clear that anxiety is correlated with internal conflict and contradiction in this way. On the other hand, this internal regulatory variable would feed into psychological mechanisms which produce the sense that one’s life is meaningful, and it should also become clear that meaning in life is correlated with psychological integration in this way. We will review the evidence for that further below.

The Psychological Entropy Framework

In order to understand why psychological integration is both important and difficult to achieve, we will review some basic ideas from the psychological entropy framework, put forward by Hirsh, Mar, & Peterson (2012). They proposed the entropy model of uncertainty (EMU), which has four major tenets:

(a) Uncertainty poses a critical adaptive challenge for any organism, so individuals are motivated to keep it at a manageable level; (b) uncertainty emerges as a function of the conflict between competing perceptual and behavioral affordances; (c) adopting clear goals and belief structures helps to constrain the experience of uncertainty by reducing the spread of competing affordances; and (d) uncertainty is experienced subjectively as anxiety… (p. 304)

In this section we will mainly discuss tenets a, b, and d, with tenet c coming back up later in our review of empirical research on meaning in life, which is most definitely promoted by having clear goals and belief structures.

Uncertainty Poses a Critical Adaptive Challenge

In order to attain our biologically relevant goals—survival, reproduction, status-attainment, affiliation, etc.—we must know how to act. But there are a potentially infinite number of ways that we could act, and we must decide from this infinite potential on one definite course of action. Sometimes this is easy. We are hungry, so we eat. We are bored, so we watch a movie. Sometimes the best course of action simply feels obvious to us, so that we don’t need to think about it at all.

But other times, the right course of action is very far from obvious. Patterns of action that worked in the past may not work in the future given changes in the environment or changes to the organism itself. A number of conflicting options may be available to an organism, and given the complexity of both the organism and the world it occupies, the proper course of action may be utterly mysterious to it. Action must be taken, however, and so uncertainty of this kind poses a real problem.

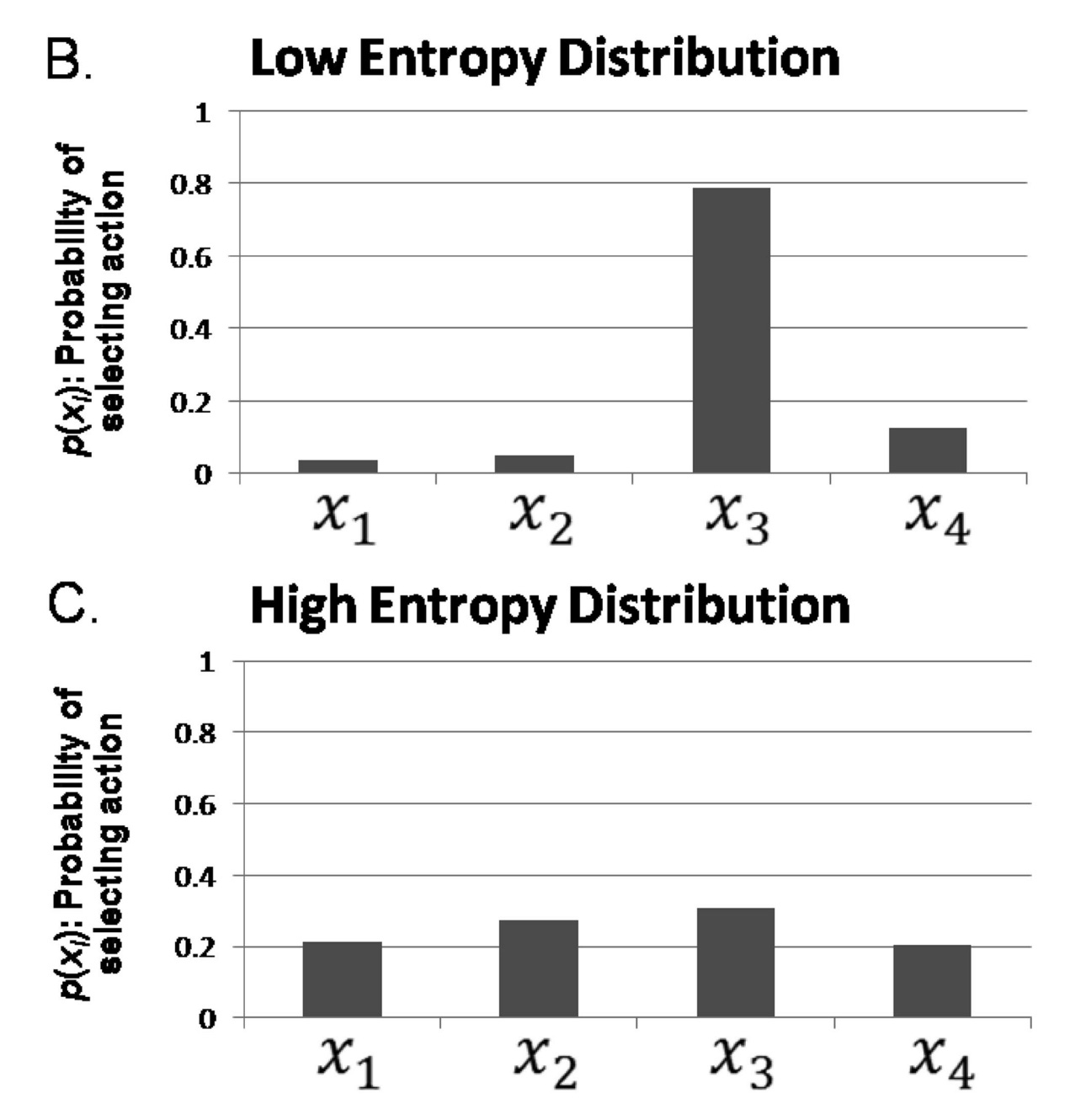

The amount of uncertainty associated with a given experience can be quantified in information-theoretical terms as entropy. The most intuitive way to think about this kind of entropy is as a probability distribution of confidence in potential courses of action. A person would have low levels of psychological entropy if there is one course of action they are very confident about, with other courses of action being of only minor consideration. A person would have high levels of psychological entropy if there are multiple courses of action they are equally confident or unconfident about.

For example, imagine someone is working a normal job as an insurance adjustor, but has dreams of being an online content creator. They have been sporadically making content for a while and the reactions have been positive, but they aren’t able to invest the amount of time and effort into their projects that would be necessary to create something truly great. They are considering quitting their job to pursue their creative work full time. On the other hand, they value the security and predictability of their 9-5, and know that their parents and other close relatives would be disappointed if they no longer had a stable job.

These are the options swimming through their mind:

Give up on their creative endeavors to focus on their chosen career path in insurance.

Quit their job to focus on their creative work.

Stay in the insurance job for another year, then decide.

Indefinitely try to do both at the same time, working weekends and nights if necessary.

A high-entropy state of mind would be one in which they had equal confidence in each of these courses of action:

25% chance of taking option 1.

25% chance of taking option 2.

25% chance of taking option 3.

25% chance of taking option 4.

This person would be extremely anxious about this decision. A low-entropy state of mind would be one in which the person had nearly full confidence in whatever course of action they had chosen to take.

1% chance of taking option 1.

97% chance of taking option 2.

1% chance of taking option 3.

1% chance of taking option 4.

This person is extremely confident that they are going to quit their job to focus on their creative work, and this person would have little-to-no anxiety about this decision. The figure below, from Hirsh, Mar, & Peterson’s 2012 paper demonstrates the difference between high and low entropy states like this, with low entropy indicating high probability of selecting a particular course of action, and high entropy indicating equal probabilities of selecting multiple courses of action.

Uncertainty & Levels of Abstraction

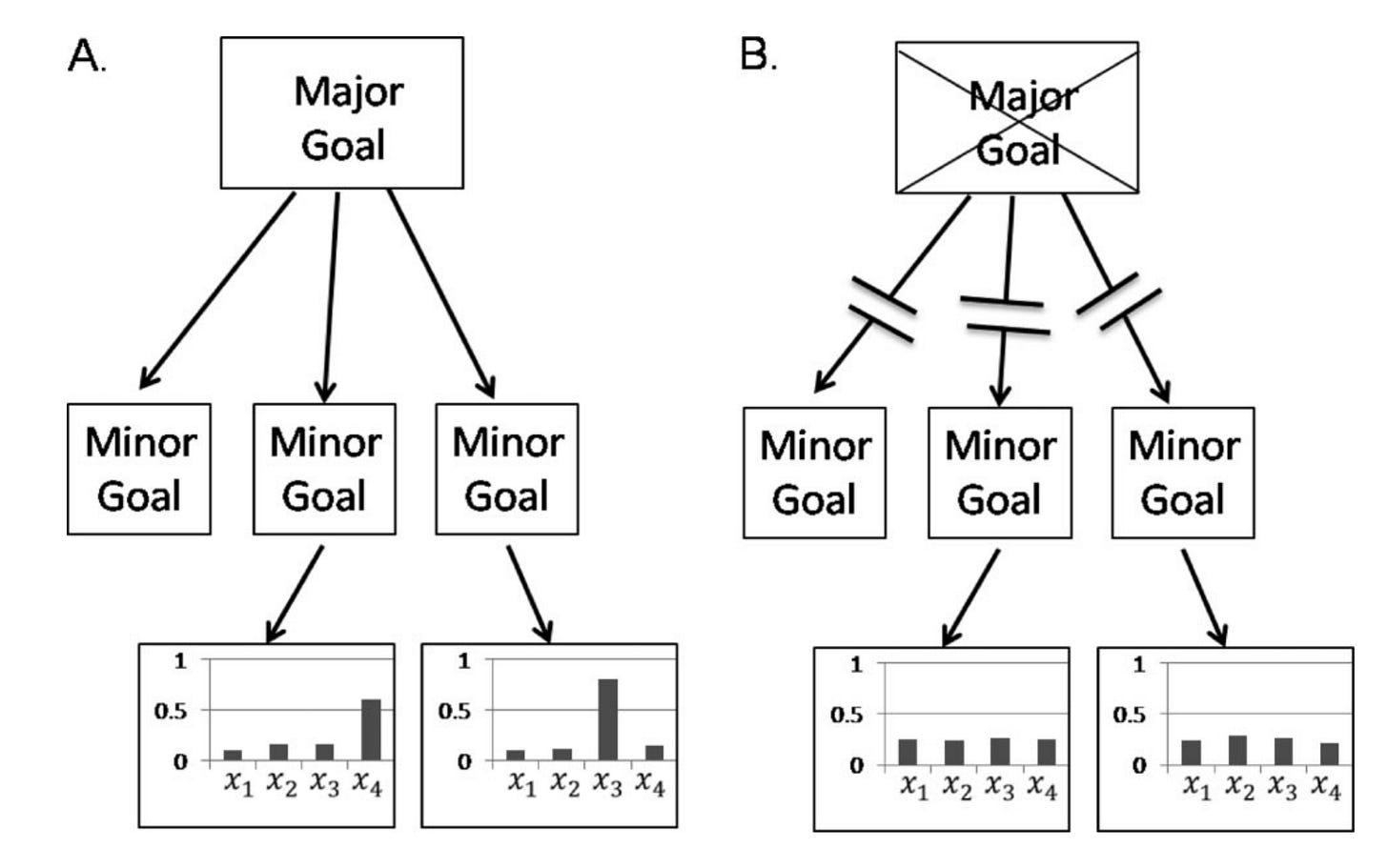

Not all uncertainty is created equal. Even maximal uncertainty about what kind of cereal you’re going to get at the grocery store doesn’t produce much anxiety except in the most neurotic of persons. The more abstract and long-term the decision is, the more entropy will be generated by uncertainty about that decision. This is because our goals are nested inside of each other, such that uncertainty about high-level goals entails uncertainty about the low-level goals nested inside of them.

For example, uncertainty about whether or not you are pursuing the right career path is going to generate a lot more entropy than your choice in breakfast cereal. That’s because your career goal, whatever it may be, has lots of sub-goals nested inside of it. If you are uncertain about your career goal, you are also uncertain about all of the sub-goals which are dependent on it. Hirsh, Mar, & Peterson (2012) comment on uncertainty about more abstract or high-level goals:

Uncertainty-inducing events that pose a threat to central life goals produce a much larger psychological response… The dissolution of these more abstract self-goals has broader implications than the loss of simple behavioral goals, so the concomitant increase of psychological entropy is greater and more widespread. Disrupting a higher order goal means that many behavioral and perceptual affordances previously constrained by this goal are suddenly allowed to vary freely. Accordingly, while challenges to lower order goals may lead to relatively minor experiences of anxiety (instantiated as a slight and temporary flattening of the distribution of possible actions and interpretive frames), challenges to an individual's higher order goals can lead to states of profound behavioral and affective destabilization… (p. 309)

In terms of this post’s thesis, this means that threats to central life goals should not only produce anxiety, but also reduce the sense of meaning in life. The figure below from Hirsh, Mar, & Peterson 2012 demonstrates why uncertainty about high-level goals generates more entropy, and therefore more anxiety (and, I propose, a greater loss in meaning), than uncertainty about low-level goals.

Uncertainty Emerges as Conflict Between Behavioral Affordances

Fear and anxiety are distinct because fear results from a different underlying psychological adaptation than anxiety (Perkins et al., 2007). A well-defined threat with a well-defined course of action for avoiding it can induce fear. If a man with a knife starts to chase after you, you will feel fear, and you will most likely run. In this case, there is little uncertainty about what the proper course of action is, and therefore little anxiety.

On the other hand, anxiety can be prompted even by apparently positive events like winning the lottery. That’s because anxiety is primarily a reaction to uncertainty about what to do. This uncertainty can be specific, associated with a clearly defined event, or general, with a less clearly defined cause. Whatever the case, anxiety results from competing behavioral affordances.

This post argues that while anxiety is the negatively valenced response to this kind of internal conflict, the subjective sense of meaning is the positively valenced response to the lack of internal conflict, i.e., internal harmony and integration. People with a well-integrated psyche feel that their lives are meaningful.

Empirical Research on Meaning In Life

Here I will review multiple lines of evidence which support the hypothesis that the felt experience of meaning in life tracks psychological integration.

The Three Facets of Meaning

There is some debate within the literature about how exactly “meaning in life” should be understood, but many researchers agree that there are three main facets: coherence, purpose, and significance (Martela & Steger, 2016). These three facets sometimes go by other names. For example, coherence is sometimes called comprehension and significance is sometimes called mattering (George & Park, 2016). But these are semantic difference only. Each facet of meaning in life is plausibly understood as an aspect of psychological integration.

Coherence/Comprehension

Coherence, also called comprehension, is quite obviously and explicitly related to psychological integration. George and Park (2016) state that:

Comprehension refers to the degree to which individuals perceive a sense of coherence and understanding regarding their lives and their experiences. To experience high comprehension is to perceive that one’s life and life experiences make sense, and that things in one’s life are clear and fit together well. We further propose that consistent and coherent meaning frameworks—that is, propositions that are cohesive and not mutually contradictory—that are capable of explaining one’s life circumstances, contribute to a sense of comprehension. (pp. 207-208)

In other words, when our understanding of the world and our self is coherent, comprehensible, and without internal contradiction, we feel that our lives are more meaningful. This involves consistency between our different propositions about what the world is like, and consistency between our experience and our propositions about what the world is like. When we experience inconsistency between our propositions, or inconsistency between our experience and our propositions, this will be felt as a threat to our sense of meaning, and will typically be accompanied by an increase in anxiety. This kind of inconsistency is often produced by traumatic events, which threaten our sense that the world is comprehensible and that we know our place in it.

Purpose

In discussing the entropy model of uncertainty, I said earlier that I would come back to the idea that having clear goal structures is an empirically validated method of reducing uncertainty. As would be expected, having clear and valued goals is an important aspect of the felt sense of meaning in life. This is what is meant by purpose. George & Park (2016) explain:

We define purpose as the extent to which individuals experience their lives as being directed and motivated by valued life goals. To experience purpose is to have a clear sense of the valued ends toward which one is striving and to be highly committed to such ends. Further, we suggest that meaning frameworks contribute to purpose in the following manner. People’s meaning frameworks—their mental representations of how things are—outline for them what ends and states are desirable and worth striving for. Specifically, meaning frameworks that specify worthy high-level goals that are central to one’s identity and reflective of one’s core values, contributes to purpose. (p. 210)

As should be obvious, having clear and valued goals plays an integrative role because having such clear goals constrains all the sub-goals and sub-routines used to attain them. If you know exactly where you are headed and you know exactly how you want to get there, you also know exactly what you should be doing each day to move forward towards your goals.

On the other hand, if you don’t know where you want to end up, you will not have much idea of what it is you ought to be doing with yourself. Behavioral affordances will appear equally valuable or equally unworthy of your attention. Should you go to school? Work on creative projects? Hang out with your friends? Spend more time dating? Find another job? Without clear and valued goals, it is unclear how you ought to spend your time and this behavioral uncertainty will be felt as a lack of purpose, and therefore as a lack of meaning. It is the felt sense of behavioral disintegration.

Significance/Mattering

In the meaning literature, significance has most often been associated with the kinds of questions Pinsof pondered about in the introduction to this post. What is my place in the cosmos? Am I contributing to something bigger than myself? Whether or not people feel that their lives are intrinsically worthwhile and valuable is clearly associated with meaning in life, but this facet has received comparatively less empirical attention than the other two (George & Park, 2016).

When the significance/mattering facet was originally proposed, it was mostly considered in the context of “cosmic” mattering. Researchers asked people whether or not they felt their lives were important in a universal sense. They ask their subjects whether they agree or disagree with statements like “Whether my life ever existed matters even in the grand scheme of the universe”, and “Even a thousand years from now, it would still matter whether I existed or not”. In other words, they are asking subjects to rate how cosmically important or special they are.

More recent research has found that interpersonal mattering is actually a more important contributor to the overall felt sense of meaning in life, and this makes a lot more sense from an evolutionary perspective (Guthrie et al., 2025). This research finds that it really matters to us whether or not we matter to the people around us. And, given the highly social creatures we are, of course it does! Numerous studies show that having valued interpersonal relationships is closely related to the felt sense of meaning in life (Guthrie et al., 2025; Hicks & King, 2009; Hicks et al., 2010; Lambert et al., 2010; 2013; Martela et al., 2018; Zadro et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2019).3

Multiple experiments have found that being socially ignored or excluded reduces the feeling of meaning in life acutely and immediately (Stillman et al., 2009; Zadro et al., 2004). This is the case even though the exclusion occurs anonymously and in the context of a totally inconsequential computerized ball-tossing game. One can imagine that being excluded in real life by people who matter to us would be felt even more acutely.

As the highly social creatures we are, being integrated socially is a necessary component of being integrated psychologically. Human beings have never been able to survive as individuals. We are born into and enculturated into a group. Being ostracized from that group is felt as intensely painful because from a historical and evolutionary standpoint, being ostracized is basically equivalent to death. If we do not matter to the people around us, there is likely something very wrong. We must find ways to be internally integrated at the same time as being externally integrated into the social world around us. Disintegration in either case is accompanied by a felt sense that our lives lack meaning.

The Three Facets Are All Integration

People seek coherent relationships—integration—within the external world (comprehension/coherence), within themselves (purpose), and between themselves and the external world (significance/mattering). All of these facets can be plausibly related to psychological adaptations which must work together in a person such that there isn’t too much conflict or contradiction between them. We must have beliefs about what the world is like, but conflict between these beliefs poses a problem, both for navigating the world and for justifying our actions to other people. We are motivated to reduce conflict and contradiction between our various beliefs about what the world is like. When we are unable or unwilling to do so, our lives feel less meaningful, which I am arguing is an indication that our lives are less integrated.

We must act within the world, but acting requires doing one thing and not doing a great many other things. In order to act effectively, we must have valued high-level goals that constrain the kinds of sub-goals we consider worthy of our attention. In other words, we must have purpose—and when we don’t, our lives feel less meaningful.

Finally, we must act in such a way that we fit in to, i.e., are integrated with, the world around us, socially or otherwise. If our beliefs or actions make us unlikeable or unsuitable to the people around us, we will feel as if we don’t matter to them, and this is empirically associated with a reduction in the felt sense of meaning in life.

The Meaning Maintenance Model

Earlier I argued that meaning in life should be considered a mood rather than an emotion, referring to the framework put forward in Marco Del Giudice’s 2021 chapter on the motivational architecture of emotions. Del Giudice argued that one important aspect of moods, as third-order coordination programs, is that moods make it possible to engage in compensatory strategies in order to maintain or regain a positive mood. We already know that people do this. For example, people may engage in binge eating or binge drinking to maintain their emotional state in the face of some personal loss or failure. Friends will say nice things to somebody in the wake of a personal loss, like a break-up or job loss, in order to raise their friend’s mood. These are compensatory strategies for regulating our moods or the moods of others. And they work! At least temporarily. Del Giudice (2021) comments that:

As third-order coordination programs, moods are not driven by specific events, but by integrative evaluations of the state of the organism in relation to the environment. In this sense, they are harder to regulate than emotions/motivations, and less susceptible to targeted strategies such as reappraisal and suppression. On the other hand, the fact that mood mechanisms integrate over multiple inputs—including the immune system, digestive system, etc.—creates some opportunities for regulation that are not available for lower-order mechanisms. For example, it becomes possible to employ compensatory strategies, so that success in one motivational domain balances out failure in another. (p. 26)

If meaning in life is a mood in this way, it should be possible for people to engage in compensatory strategies to maintain the felt sense of meaning in life. This is the subject of the influential Meaning Maintenance Model (Heine et al., 2006; Proulx & Heine, 2010; Proulx & Inzlicht, 2012), which provides evidence and theory indicating that people do, in fact, engage in such compensatory strategies when some aspect of their meaning in life is threatened. While there are multiple compensatory strategies people may use to affirm their meaning in the face of some threat to it, the most commonly studied one consists of strengthening or positively affirming some other, unrelated source of meaning in the face of some threat to global meaning.

For example, in one study participants who read an absurd Kafka parable (which presumably threatened some aspect of their psychological integration) affirmed an alternative meaning framework more than did those who read a meaningful parable (Proulx et al., 2009). In other studies, people who were presented with threats to their self-esteem, reminders of mortality, or reminders of the injustice of the world also affirmed alternative meaning frameworks more than controls (Heine et al., 2006).

Interestingly, one set of studies found that this fluid compensation was reduced or absent in participants who were given a dose of acetaminophen (i.e., Tylenol; pain killer) right before the study (Randles et al., 2013). This would suggest that it is the pain caused by threats to someone’s meaning which leads them to compensate by clinging more tightly to other sources of meaning. This means that the compensation is largely palliative, done to assuage the pain that comes along with doubting some aspect of the beliefs and values that provide meaning.

I must admit that I am skeptical of much of the research on meaning maintenance. These are the kinds of relatively low N studies, performed on undergraduates, with relatively small effect sizes, and relatively counter-intuitive results, that tend not to survive replication attempts. On the other hand, the idea that people engage in compensatory strategies to maintain psychological integration is not counter-intuitive at all, and is well-supported both by empirical literature and life experience. To put it bluntly, I think the Meaning Maintenance Model is broadly correct even if some of the studies that have been used to test it are underpowered and may not hold up to scrutiny.

Having Meaning Vs. Searching for Meaning

I said earlier that if anxiety is the negative counterpart of meaning, then we should find that anxiety is negatively correlated with the presence of meaning in life, and positively correlated with being on a search for meaning. And that is the case. Several studies have found an inverse correlation between the presence of meaning and anxiety (Yek et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2021; Ostrafin et al., 2021). One relatively large N study found a positive correlation between the search for meaning and anxiety (Yek et al., 2017). Two meta-analyses published in 2023 confirm the finding that meaning in life is negatively correlated with anxiety (He et al., 2023; Boreham & Schutte, 2023) while one of these also confirmed that the search for meaning is positively correlated with anxiety (He et al., 2023).

Anxiety has already been argued to be the affective counterpart to psychological disintegration, or conflict between behavioral affordances (Hirsh et al., 2012; Hirsh & Kang, 2016). My argument is simply that the felt sense of meaning in life is the positively valenced opposite of anxiety. When we are psychologically integrated such that there is little contradiction or conflict between behavioral affordances, we feel that our lives are meaningful. The negative correlation between anxiety and meaning in life supports this view.

On the other hand, we should be more motivated to search for meaning when we are psychologically disintegrated. The positive correlation between the search for meaning and anxiety supports this view.

Support From Psychedelic Research

Many people have experienced intensely meaningful moments in life, whether they are felt during a creative endeavor, a competitive victory, the birth of a child, a sexual experience, or whatever. Abraham Maslow called these peak experiences, and they are always felt as intensely meaningful and self-justifying. Simply having the experience justifies whatever work or pain went into the process that culminated in the experience itself.

The problem with studying these kinds of meaningful experiences is that they have been impossible to reproduce in a laboratory environment. Up until recently, there has been no way for researchers to reliably produce peak experiences in their research subjects so that they can be studied experimentally. That was the case up until about 15 years ago when restrictions on research with psychedelic drugs was loosened up, and well-funded research programs began, especially on psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms.

In high enough doses, under controlled settings, psilocybin reliably produces intensely meaningful peak experiences. People tend to rate the psilocybin experience as among the top five most meaningful experiences in their life, right up there with the birth of a child (Griffiths et al., 2006). These experiences induce a number of long-term changes in the subjects, most of which would be considered positive changes by most people. The experience reduces anxiety, depression, and authoritarian political views while increasing openness and the feeling of connectedness to nature, and these changes are both substantial (i.e., the effect sizes aren’t small) and last up to a year or longer (Griffiths et al., 2008; Griffiths et al., 2011).

Connectedness As Integration

Interestingly, many of these effects are mediated by an increased sense of connectedness reported by subjects during and after the psychedelic experience (Watts et al., 2017; Carhart-Harris et al., 2018). Carhart-Harris and colleagues (2018) state that:

A sense of disconnection is a feature of many major psychiatric disorders, particularly depression, and a sense of connection or connectedness is considered a key mediator of psychological well-being, as well as a factor underlying recovery of mental health. One of the most curious aspects of the growing literature on the therapeutic potential of psychedelics is the seeming general nature of their therapeutic applicability, i.e. they have shown promise not just for the treatment of depression but for addictions, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder. This raises the question of whether psychedelic therapy targets a core factor underlying mental health. We believe that it does, and that connectedness is the key…

Post-treatment, participants referred to feeling reconnected to past values, pleasures and hobbies as well as feeling more integrated, embodied and at peace with themselves and their often troubled backgrounds. It is a working hypothesis of ours that connection-to-self is a bedrock from which connection to others and the world can follow most naturally.

The research on the sense of connectedness associated with the psychedelic experience has been driven by the open-ended reports of the participants themselves, who often claim to feel increasingly connected to themselves, their past, other people, and the world around them both during and after the trip. Later research confirmed that this sense of connectedness mediates the therapeutic benefits of the psychedelic experience (Watts et al., 2017).

My contention is that this felt sense of connectedness is the phenomenological concomitant of increased psychological integration. The trip is felt as intensely meaningful, and this meaning is—I would argue—indistinguishable from the sense of connectedness. They are different ways of describing the same underlying process of psychological integration.

We have some ideas about how neurobiology and cognitive effects of psychedelics may support psychological integration, by relaxing high-level priors or beliefs that may currently be preventing integration (Carhart-Harris & Friston, 2019), but exploring that process in detail is outside the scope of what I’m doing here.

The Dark Side of Meaning

All of what I’ve said so far sounds like the pursuit of meaning is all good and no bad, all upside with no downside. This is not the case. Empirical research has revealed that there are ways to increase one’s sense of meaning in life that many of us would consider pathological or anti-social. The two I will focus on here are psychotic delusions and quasi-religious political ideologies like fascism and communism. Both psychotic delusions and ideologies can increase psychological integration, though they come with obvious costs.

Delusions Are Meaningful

Clinical delusions are often thought of as incomprehensible and meaningless. This may be true for an outsider trying to understand why someone thinks the CIA is beaming thoughts into their brain through cell phone towers, or that Martians are poisoning the drinking water, or that they are the reincarnation of the Buddha, or whatever. But there is evidence that, for the person experiencing the delusion, these strange beliefs can help to make sense of their unusual experiences, and therefore provide a sense of psychological integration, even if it’s a pathological one.

According to Rittunano & Bortolotti (2021):

There are at least two ways in which delusions can be thought to confer meaningfulness: delusions emerging in the context of schizophrenia can help the person make sense of unusual experiences that would otherwise seem inexplicable and cause uncertainty and anxiety; and delusions emerging as a response to trauma or adversities can be conceived as protective responses to disruptive life events, making the person’s experience more bearable and especially providing a sense of purpose that helps keep depression at bay. (p. 955)

In one study, patients with elaborated delusions scored higher than patients in remission, rehabilitation nurses, and Anglican ordinands in the ‘purpose in life’ test and the ‘life regard’ index (Roberts, 1991). Both of these tests are widely regarded as reliable means for measuring important aspects of the sense of meaning in life. In a follow-up paper, the author of that study said that:

Delusion formation can be seen as an adaptive process of attributing meaning to experience through which order and security are gained, the novel experience is incorporated within the patient’s conceptual framework, and the occult potential of its unknownness is defused [...] Lansky [...] speaks for many in asserting that ‘Delusion is restitutive, ameliorating anxieties by altering the construction of reality’. (Roberts, 1992, pp. 304–305 abridged)

In other words, unusual experiences can psychologically disintegrate somebody because those experiences cannot be incorporated into their current belief system. Delusions may function, in part, as compensatory frameworks that help individuals integrate anomalous experiences that would otherwise be too distressing or inexplicable. To be sure, they are false beliefs, but they still appear to integrate the person’s unusual experiences better than whatever alternatives are available.

Ideologies Are Meaningful

Ideologies we would consider to be violent or hateful can confer a sense of meaning in life. A 2018 review paper put forward “significance quest theory”, which explains violent extremism by asserting that:

…the need for personal significance—the desire to matter, to “be someone,” and to have meaning in one’s life—is the dominant need that underlies violent extremism. A violence-justifying ideological narrative contributes to radicalization by delineating a collective cause that can earn an individual the significance and meaning he or she desires, as well as an appropriate means with which to pursue that cause. Lastly, a network of people who subscribe to that narrative leads individuals to perceive the violence-justifying narrative as cognitively accessible and morally acceptable. (Kruglanski et al., 2018 p. 107)

To be clear, the quest for significance doesn’t only underlie adherence to violent or hateful ideologies, but can potentially underlie any extreme activity undertaken for a perceived worthy cause. Either way, collective ideologies can provide meaning in terms of all three facets discussed earlier.

They provide coherence by providing us with a narrative about what the world is like, why bad things happen, and what our place in the world is. They provide purpose by giving us a clear idea of what we ought to be doing to make the world a better place—even if that means engaging in violent or self-destructive behavior. Finally, they provide significance by telling us that we are participating in some kind of valued endeavor, whether it’s the establishment of the caliphate, the kingdom of God, or a communist utopia. The supposed ends always justify the means.

A set of two studies also found that collective, but not individual, hatred also confers a sense of meaning in life (Elnakouri et al., 2022). Hatred directed at groups, but not at individuals, conferred a heightened sense of meaning in life through increased determination, eagerness, and enthusiasm, and through decreased feelings of inner conflict, uncertainty, and confusion. Basically, hatred for an out-group gives people something purportedly valuable to do, which confers a sense of purpose and coherence.

My point here is that there all sorts of seemingly pathological ways that people can attain a sense of meaning in life because there are different pathological ways to achieve greater psychological integration. Meaning in life is not an unadulterated good, and neither is psychological integration. It feels good, of course, but that good feeling can still be in the service of anti-social or pathological aims. To put it in David Pinsof’s terms, the sense of meaning in life is real, but we can absolutely bullshit ourselves into feeling as if our lives are meaningful. Not all meaning is created equal.

Conclusion

Everything above plausibly indicates that the felt sense of meaning in life is tracking psychological integration—the extent to which our psychological adaptations, values, goals, beliefs, perceptions, and so on are functionally integrated such that there is little conflict or contradiction between them. The downstream result of disintegration is behavioral uncertainty, when no behavioral affordances stand out as being obviously correct. This kind of behavioral uncertainty results in anxiety.

The downstream result of psychological integration is the sense that we know what the world is like, what our place in the world is, and how it is that we matter to the world and to other people. The result is a sense that our lives have coherence, purpose, and significance—in other words, that they are meaningful. The felt sense of meaning is therefore the output of a psychological adaptation that tracks the degree of psychological integration.

I only found one study looking at the heritability of meaning in life, and although the measured heritability was between 20-30% for both presence of meaning and search for meaning, these were non-significant due to a low sample size (Steger et al., 2011). We can surmise that given a reasonable sample size, these constructs would be found to be moderately heritable like nearly every other construct in psychology. Twin studies consistently find a heritability of between 30-60% for the presence of anxiety (Purves et al., 2019). It’s likely that everyone has a baseline level of meaning that they feel, and a baseline tolerance for lack of meaning. In other words, some people are going to be more naturally psychologically integrated than others, and some people will need to be more psychologically integrated to feel good than others. This means that some among us will almost certainly be able to tolerate more psychological disintegration without feeling bad about it, and others will constantly be on a search for meaning as its absence will be more acutely felt. These are all directions for future research.

There are plenty of openings to study meaning in life from an evolutionary perspective, and plenty of unanswered questions left for budding graduate students out there to explore. I hope that any evolutionary psychologists reading this will come away with a better understanding of how research on the meaning in life construct can be understood from an evolutionary perspective. I hope everyone else got something useful out of it too.

If anyone out there wants to publish something like this, just email me or message me on here and I’ll be a co-author.

Cybernetics provides a more plausible understanding of the mind than computational models based on decision-rules. More recently, Bayesian models, which are a species of cybernetics, have risen in popularity among cognitive scientists, and this too provides a more plausible view of the mind than the ‘input —> computation via decision-rules —> output’ model often used by evolutionary psychologists.

See Badcock et al., 2019 for an interesting synthesis of Bayesian cognitive science with evolutionary psychology.

Still, acting as if the mind uses decision-rules has led to interesting research, so the computational model has its uses even if it is ultimately wrong or incomplete.

Find references for all these in the bibliography of Guthrie et al., 2025.

Good critique of my hypothesis in that piece. But that hypothesis was more about meaning of life discourse than the felt experience of meaningfulness. I actually have a different hypothesis for the felt experience of meaningfulness I propose in my post “Happiness Is Bullshit Revisited.” I’m curious what you think of it. Here is the relevant bit: “We want valuable long-term goals. From an evolutionary perspective, such goals would include rearing offspring to maturity, becoming a valued member of our community, ascending a social hierarchy, or outcompeting rival groups for power and resources. These goals give us a sense of “meaning,” which explains why people find meaning in family, altruism, careerism, and (depressingly) hatred of outgroups. The function of “meaning,” I surmise, is to enable short-term fitness costs in pursuit of long-term fitness gains. The more “meaningful” a goal seems, the bigger the short-term sacrifices we should be willing to make to achieve it.

What this suggests is that having valuable long-term goals is good for you, evolutionarily. If you have no children to care for, no viable path to high status, no way to make yourself valuable to your community, or no tribe to rally, then you’re in a bad spot, evolutionarily. You’re adrift, aimless. Maybe this corresponds to feelings of “depression” or “ennui.” I’m not sure.

But the point is: we’d like to avoid this state. And we’d like to be in the opposite state: the state of pursuing valuable long-term goals (and, ideally, making good progress on them). Confusingly, a lot of people call this long-term-goal-pursuing state “happiness.” But more often, people call it “meaning” or “purpose.” Whatever you decide to call it, I’m okay saying we want it.

But wait. That doesn’t mean we want the mere feeling of it. We don’t want to be tricked into thinking we’re raising healthy children or becoming valuable members of our communities. It would be very bad if somebody lied to us about the health of our children or flattered our egos while secretly despising us. Even if we’d be happier living a lie, we’d prefer to be in touch with reality.

So again, we’re not seeking vibes in our heads. We’re seeking real things in the world. When given the choice between real meaning and fake meaning, we’re going to choose real meaning, even if the fake meaning feels nicer.

I resonate with your thesis: “the subjective sense of meaning in life is the output of an internal regulatory variable tracking the degree of psychological integration, or lack of conflict, between psychological adaptations in addition to the values, beliefs, goals, and perceptions that facilitate the pursuit of adaptive outcomes.”

It seems consistent with Dan Siegel’s definition of mind[ing]: “The process of regulating energy and information, that is emergent, self-organizing, embodied, and interpersonal.” Ultimately, he defines health as the integration of internal states and behavior choices, consistent with environmental conditions. A state which feels like peace of mind.

One can only hope that such a state will help us evolve through our current existential bottleneck.