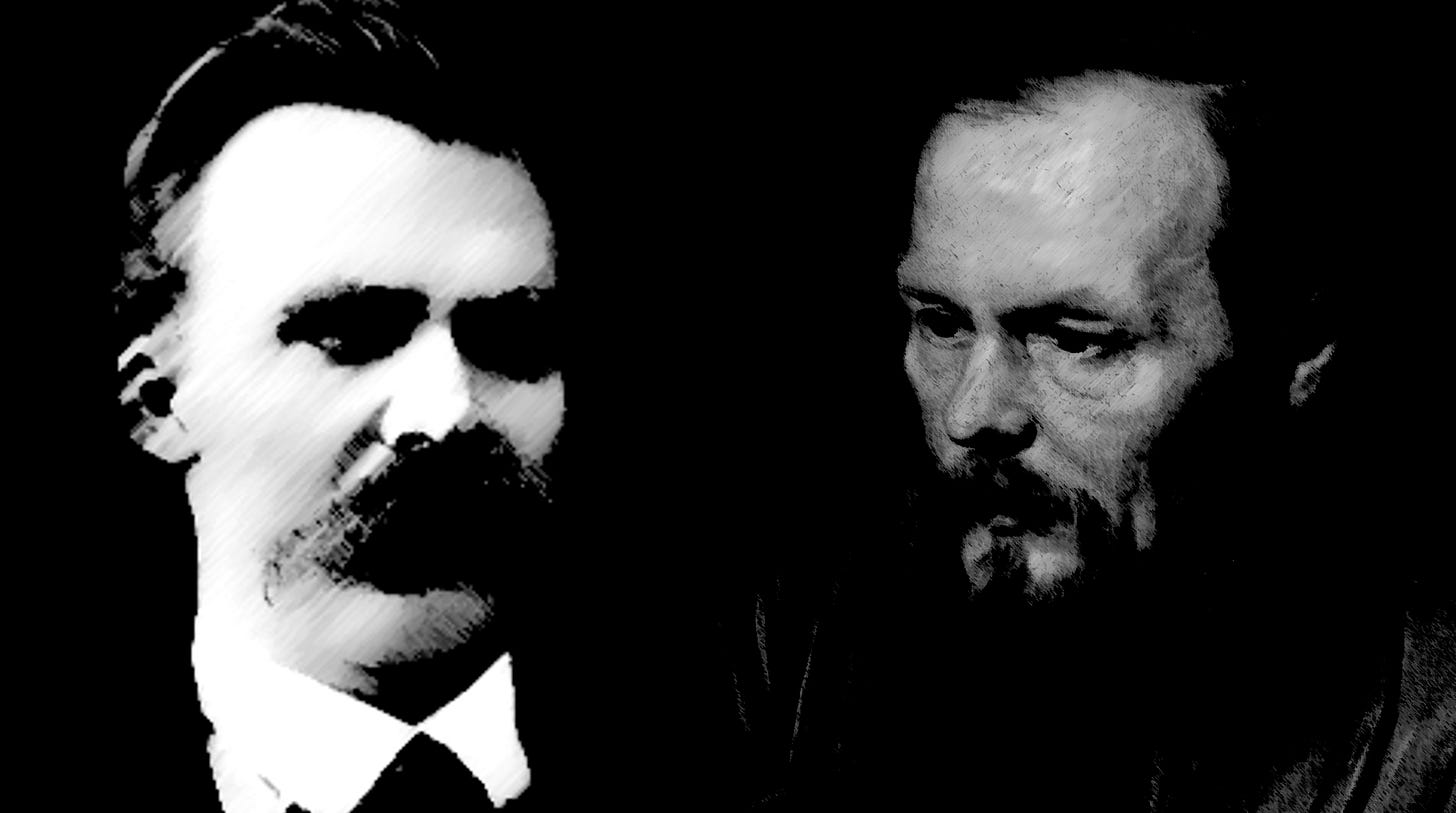

Nietzsche vs. Dostoevsky

Truth and Love

Two Giants

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) was a German philosopher best known for his uncompromising critiques of morality, religion, and culture. He challenged the foundations of Western values and sought to build an alternative to traditional faith and morality. His works—Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Beyond Good and Evil, and On the Genealogy of Morals among them—remain some of the most provocative and influential texts in modern philosophy. Nietzsche’s thought ranges from the aphoristic to the poetic, but always circles around a central concern: how to live fully and truthfully in a post-religious world.

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881) was a Russian novelist whose works probe the depths of the human soul under the weight of suffering, freedom, and faith. His great novels—Crime and Punishment, Demons, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov—stand at the intersection of theology, psychology, and existential philosophy. Dostoevsky’s characters wrestle with the meaning of evil, the possibility of redemption, and the demands of love in a fractured world. Though he wrote as an artist rather than a philosopher, his psychological and theological insights have made him one of the most important figures in modern intellectual history.

A Surprising Kinship

On the surface, Nietzsche and Dostoevsky appear to be diametrically opposed. One is a great critic of Christianity and the other is apparently an apologist for it. And yet Nietzsche regarded his discovery of Dostoevsky as one of the greatest events of his later career. He remarked that Dostoevsky was the only psychologist from whom he had something to learn.

In this brief post, I want to explore the similarities and apparent differences between Nietzsche and Dostoevsky. Their philosophies share profound points of contact, but there is also an important difference of emphasis. That difference, however, is not irreconcilable—it is a tension that can and should be overcome.

Both Critique the Priestly Takeover of Christianity

Dostoevsky was critical of Catholicism, believing that Rome had transformed Christianity into an empire of worldly power built on supposed miracles and worldly authority—precisely what Christ had rejected when he resisted the Devil’s temptations in the wilderness. In his parable of the Grand Inquisitor, embedded within his book The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky portrays the priestly Inquisitor as a man who consciously inverts Christ’s message, making it palatable to the masses rather than directed only at the few who are strong enough to bear it.

And make no mistake—this is a deviation from the message of Christ, even within the canonical gospels. Christ is explicit that his message is for the few, not the many:

Enter by the narrow gate. For the gate is wide and the way is easy that leads to destruction, and those who enter by it are many. For the gate is narrow and the way is hard that leads to life, and those who find it are few. (Matthew 7:13–14)

The Grand Inquisitor accuses Christ of demanding too much: that people accept freedom, take responsibility, and embody love even toward their enemies. Most people are incapable of such things. To justify the Church’s path, he claims it is better to rule by offering bread, spectacle, and obedience than to burden people with freedom and responsibility.

Nietzsche, in The Genealogy of Morals, makes a strikingly similar claim about the role of the ascetic priest. The priest ministers to the weak and sickly by reinterpreting their suffering as meaningful, redirecting their ressentiment away from rebellion against society and inward against themselves, sublimating it into guilt and sin. Like the Grand Inquisitor, the ascetic priest is a shepherd to the weak, offering them palliatives to help them endure life without becoming dangerous or unruly.

Both figures exploit human weakness as the basis of their authority. Both explicitly rule over the weak and sickly by offering comfort and stability in exchange for submission. Both reframe suffering in a way that preserves social order. And both stand as rivals to human greatness and human freedom.

The ascetic priest and the Grand Inquisitor are, in fact, the same character. This convergence helps to explain why Nietzsche felt such a kinship with Dostoevsky when he finally did encounter him in the same year in which he was writing The Genealogy of Morals. Nietzsche recognized that Dostoevsky had observed the same pathology that he himself had been working to expose.

Both Understood the Psychology of Ressentiment

Nietzsche’s understanding of ressentiment—of the resentment that turns inwards and curdles over time when it is unable to be expressed openly—is perfectly exemplified by Dostoevsky’s underground man. The parallels are striking. For example, both discuss the self-contempt that underlies the psychology of ressentiment.

It is clear to me now that, owing to my unbounded vanity and to the high standard I set for myself, I often looked at myself with furious discontent, which verged on loathing, and so I inwardly attributed the same feeling to everyone. (Notes From the Underground pp. 46-47)

Where does one not encounter that veiled glance which burdens one with a profound sadness, that inward-turned glance of the born failure which betrays how such a man speaks to himself—that glance which is a sigh! “If only I were someone else,” sighs this glance: “but there is no hope of that. I am who I am: how could I ever get free of myself? And yet—I am sick of myself!” (GM III. 14)

Both perceive that the most resentful among us are characterized by a general, constitutional kind of sickness.

I am a sick man.... I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man. I believe my liver is diseased. However, I know nothing at all about my disease, and do not know for certain what ails me. (NU p. 7)

The sick are man’s greatest danger; not the evil, not the “beasts of prey.” Those who are failures from the start, downtrodden, crushed—it is they, the weakest, who must undermine life among men, who call into question and poison most dangerously our trust in life, in man, and in ourselves. (GM III. 14)

Dostoevsky described ressentiment and its dangers in narrative form while Nietzsche fleshed out the underlying psychology.

Divergences in Temperament

And yet, despite this convergence, there are profound divergences in their temperament and outlook. Here I want to put forward a hypothesis about the nature of those divergences.

In reality, both Dostoevsky and Nietzsche were profoundly influenced by Christianity, and were exemplifications of Christian values in their own way. This may sound paradoxical in Nietzsche’s case, since he was a conscious and brutal critic of Christianity, but his lineage and biography show how deeply he was affected by it. Nietzsche was born the son of a pastor. His father’s father and his mother’s father were both pastors, as were many of his recent ancestors. As a child, his nickname was “the little pastor,” since his peers assumed he would one day follow in his father’s footsteps. In a sense, I would argue that he did—though not in the way anyone expected.

Love and Truth

Within Christianity, two values stand out as supreme: love and truth. Jesus Christ died for love—the Agapic love he promoted in parables like that of the Good Samaritan—and his unwillingness to renounce his truth, even in the face of torture and death.

In his stories, Dostoevsky exemplifies the strand of Christianity rooted in love—agapic, forgiving, redemptive love. Nietzsche’s philosophy embodies the other strand: the radical pursuit of truth. Nietzsche loved the truth so much that he was even willing to question the value of truth itself. He wanted to know the truth about truth. He wanted to test his deepest values and beliefs by bringing them to the light, no matter the cost. He carried the pursuit of truth to its most radical conclusions. Even his critique of morality was rooted in a morality of truth, and he was conscious of this fact:

…in this book faith in morality is withdrawn - but why? Out of morality! Or what else should we call that which informs it - and us? for our taste is for more modest expressions. But there is no doubt that a 'thou shalt' still speaks to us too, that we too still obey a stern law set over us - and this is the last moral law which can make itself audible even to us, which even we know how to live, in this if in anything we too are still men of conscience: namely, in that we do not want to return to that which we consider outlived and decayed, to anything `unworthy of belief, be it called God, virtue, truth, justice, charity… (Daybreak 4)

Nietzsche understood himself as the self-sublimation of Christian morality by Christian morality—the overcoming of Christian lies by the cultivation of Christian truthfulness. Dostoevsky, for his part, carried the pursuit of love to its furthest conclusion.

Seen this way, Nietzsche and Dostoevsky represent two strands of Christianity itself, two values that are ultimately compatible but have often been in tension throughout the history of the Western world. For two thousand years, the Western tradition has been shaped by the interplay, and sometimes the rivalry, between love and truth. Nietzsche and Dostoevsky bring each of these to its highest intensity.

Those who see Dostoevsky and Nietzsche as fundamentally incompatible have missed the point. A value system without love for the truth collapses into self-contradiction—it is incomplete at its core. But the reverse is also true: pursuit of truth that is not in the service of love becomes self-contradictory as well. It, too, is incomplete.

I believe that Dostoevsky and Nietzsche both embodied this apparent contradiction. The overlap in their work reflects this fact. Their emphases were different, but not mutually exclusive. Dostoevsky clearly loved the truth, though his focus was on love. Nietzsche clearly pursued the truth, but he did so in the service of love. Nietzsche’s love for humanity was expressed not as a love for what humanity is, but what humanity could become. But that is agapic love, to see the potential in something or someone and to wish to bring that potential out of them. That’s what Nietzsche explicitly wanted for humanity. Some may deny this, but only because they do not know Nietzsche well enough.

People misunderstand Nietzsche’s will to power as being some kind of sociopathic will to control, manipulate, and dominate—but this is contrary to pretty much everything Nietzsche said about it. The powerful person is magnanimous and courageous—willing to endure risk, suffering, or even destruction in the service of a higher cause, most especially in the service of creation.

Nietzsche was a compassionate man, though he would have been ashamed to wear his compassion on his sleeve (only those who are insecure about their compassion do this). His compassion was directed into the pursuit of truth. The highest expression of his compassion was to speak the brutal, ugly, disgusting, and even destructive truth—truth that wounded himself and others—because he believed that only through truth was actual healing possible. Nietzsche understood that the truth can make you sick, but he also believed that this sickness was only the precursor to a higher form of health. In this sense, he saw himself as a cultural physician, seeking to heal the sicknesses of his culture through truth. Dostoevsky, by contrast, sought to heal his culture through love. Again, to see some deep and incompatible conflict between these approaches is to fail to see the ultimate unity of truth and love.

They are not fundamentally incompatible—at least not in the way they are often portrayed. Rather, they represent two poles of the same inheritance.

Christ Versus Christianity

It is important to understand that Nietzsche’s critique of Christianity was not a critique of Jesus himself. Indeed, Nietzsche saw Jesus as the only true Christian, and posited that Christ himself taught a way of life that was nearly opposite to what Christianity became.

What turned Christianity away from life? That priestly, hateful man named Saul, who became Paul. A number of modern scholars of Christianity have come to nearly the exact same conclusion as Nietzsche, totally independently of him. For example, the scholar of early Christianity James Tabor wrote in his 2010 book Paul and Jesus that the understanding of Christianity in which Jesus is a cosmic savior, that salvation rests on a belief in his resurrection, had nothing whatsoever to do with Jesus himself, and comes entirely from Paul:

… such an understanding of the Christian faith, confessed by millions each week in church services all over the world, originates from the experiences and ideas of one man—Saul of Tarsus, better known as the apostle Paul—not from Jesus himself, or from Peter, John, or James, or any of the original apostles that Jesus chose in his lifetime. And further, I maintain that there was a version of “Christianity before Paul,” affirmed by both Jesus and his original followers, with tenets and affirmations quite opposite to these of Paul. (Tabor, 2010)

Nietzsche’s critique was of the structure that arose in the wake of Christ’s death, a structure Nietzsche believed had distorted the original message, and turned it into something that was close to its opposite. He traced this distortion to Paul, who laid the foundations of the Christianity we know today. Nietzsche’s critique is thus radical and far-reaching—but it is not fatal, at least if one is willing to distinguish Christ from Paul.

Of course, mainstream Christians are entirely attached to the version of Christianity put forward by Paul, and have been for nearly the last 2,000 years. Understanding Nietzsche would require rejecting Paul (or at least treating him as a regular human being with an agenda, character flaws, and so on) and that’s just not going to happen for the average Christian. So much the worse for them.

Dostoevsky, for his part, never singled out Paul, but he too critiqued institutional Christianity, and for many of the same reasons. His parable of the Grand Inquisitor offers a picture of how Christ’s radical message of freedom and love could be inverted into an authoritarian system predicated on miracle, mystery, and priestly authority. In this sense, Dostoevsky and Nietzsche converge more deeply than they diverge.

Two Sides of the Same Coin

Our task, then, is not to choose between Dostoevsky and Nietzsche. That is a misunderstanding. We can and should learn from both of them. They can both help to overcome the false dichotomy of Logos and Agape, truth and love. Nietzsche was a prime exemplification of the uncompromising pursuit of truth. Dostoevsky was a prime exemplification of Agape—the fore-giving love (i.e., love that gives before the person has done anything to “earn” it) embodied by Christ. The challenge before us is not to side with one or the other, but to overcome the apparent dichotomy between them, and to realize that truth and love are mutually necessary as two sides of the same coin.

For Christians, that would involve dropping a lot of the baggage introduced into Christianity by Paul, most especially the idea that salvation comes from belief (e.g., Romans 10:9-10). I won’t hold my breath.

I do find Paul's writing quite beautiful...I don't know too much about how he's interpretted by the church though. It is pretty nuts that so many of his letters have been canonized in the bible, as just one author! (although I think not everything was written by him directly, some is "inspired" by him but written by others. Not sure how that works though.)

Wow what a read. Are there any more resources of a pre-Pauline Christianity?