Is the World Mechanism or Music?

A brief commentary on Nietzsche's "The Gay Science" 373

This is not a full article, but rather some thoughts on a passage from Nietzsche that I wanted to write down and share. Because this is not a full article, I am going to assume you have some familiarity with my previous work (I will provide links to fill in the gaps).

In The Gay Science 373, Nietzsche said:

A “scientific” interpretation of the world, as you understand it, might therefore still be one of the most stupid of all possible interpretations of the world, meaning that it would be one of the poorest in meaning. This thought is intended for the ears and consciences of our mechanists who nowadays like to pass as philosophers and insist that mechanics is the doctrine of the first and last laws on which all existence must be based as on a ground floor. But an essentially mechanical world would be an essentially meaningless world. Assuming that one estimated the value of a piece of music according to how much of it could be counted, calculated, and expressed in formulas: how absurd would such a “scientific” estimation of music be! What would one have comprehended, understood, grasped of it? Nothing, really nothing of what is “music” in it! (GS 373)

There is a long-standing clash in Western culture between two conceptions of what the world is really like at bottom. On the one hand are the mechanists, who implicitly or explicitly believe that reality can be totally understood in terms of efficient causation (i.e., billiard ball causation) and therefore see the world only in terms of mechanism. For them, the world must be something like a watch or a computer because that is the most apt analogy for a world that only allows for efficient causation. As the philosopher Alicia Juarrero pointed out in her great book Dynamics in Action, formal and final causation have been essentially banished from Western philosophy, at least since Newton.

Aristotle's four causes are final cause (the goal or purpose toward which something aims), formal cause (that which makes anything that sort of thing and no other ), material cause (the stuff out of which it is made), and efficient cause (the force that brings the thing into being). Explaining anything [for Aristotle], including behavior, requires identifying the role that each cause plays in bringing about the phenomenon…

Because he had more than one type of cause to draw on, Aristotle was able to explain voluntary self-motion in terms of a peculiar combination of causes. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, modern philosophy had discarded two of those causes, final and formal. As a result, purposive, goal-seeking and formal, structuring causes no longer even qualified as causal; philosophy restricted its understanding of causality to efficient cause. And then, taking its cue from Newtonian science, modern philosophy conceptualized efficient causality as the push-pull impact of external forces on inert matter. (Juarrero, 2002 p. 2)

In the opening quotation, Nietzsche is talking about the worldview which says that “the push-pull impact of external forces on inert matter” is the only true form of causation in the universe. This is the mechanistic worldview.

While there are some sophisticated thinkers who adhere to some version of this worldview (e.g., Daniel Dennett), I am going to quote something that is a little less sophisticated in order to get an overview of the assumptions inherent to a purely mechanistic worldview. Michael Graziano is a neuroscientist who is most well known for his “attention schema theory” of consciousness. He describes his idea as a “mechanistic theory of subjective awareness”.

Graziano doesn’t believe in the reality of “subjective experience”. He describes the motivations behind his disbelief clearly in a 2019 paper called “We are machines that claim to be conscious”:

One cannot push on subjective experience and measure a reaction force, scratch it and measure its hardness, or put it on a scale and measure its weight. It does not exist on those physical dimensions. In the sense of its physical non-measurability, subjective experience is non-physical, or even metaphysical in the strict sense of being above or outside the physical. This ethereal nature of subjective experience is precisely why it has been so difficult to understand. But, objectively speaking, the phenomenon that faces us is much simpler. A brain-controlled agent constructs a self-description and on that basis makes claims about itself. There is no rational reason to suppose the claims are literally accurate. (pp. 1-2)

When Nietzsche said that ‘a scientific interpretation of the world might still be one of the most stupid of all possible interpretations of the world’, this is basically what he had in mind. Graziano’s worldview, in which one must be able to measure something’s reaction force or hardness in order for it to be counted as real (and therefore considers experience itself to be unreal), is one of the most stupid possible interpretations of the world. Interestingly, however, this interpretation nearly always comes from the minds of otherwise intelligent people (I do not doubt that Graziano is an intelligent, well-educated man). What is going on? We’ll come back to that.

There is another tradition within Western culture which is in opposition to the mechanistic worldview. This tradition tends to see the world as being more like music than like a watch or a computer. People like Henri Bergson and Carl Jung fall into this tradition. The most obvious representatives of this tradition in modern discourse are Jordan Peterson and Iain McGilchrist. I’m going to quote them here to give an idea of how this type of person sees the world. JBP said that:

We don’t understand the world. I do think the world is more like a musical masterpiece than it is like anything else, and things are oddly connected. Now I know that sounds New Agey and it sounds metaphysical, but I’m saying bluntly that this is speculative. I’m feeling out beyond the limits of my knowledge. I’m not willing to dismiss the mysterious. -JBP (from here: Akira the Don, The Mysterious).

Jordan Peterson and Iain McGilchrist had a discussion about this in their first public conversation. I attached an image of part of the transcript below.

Jordan Peterson and Iain McGilchrist agree that music is a representation or presentation of “the ultimate reality of the cosmos”. They agree that music “is at the core of the whole cosmic process”. Weird. I’m going to go out on a limb and assume that somebody like Michael Graziano wouldn’t find this view of things compelling.

For lack of better terms, I’m going to refer to these as the mechanistic and musical worldviews. You may guess, correctly, that I fall into the latter camp. I think the world is more like music than anything else. I think that the kind of mechanistic materialism espoused by Graziano and others is absurd. At the same time, I recognize that many otherwise intelligent people would see my worldview as equally absurd.

I am not going to attempt to reconcile these views here. I am going to put forward a hypothesis as to why the mechanistic worldview is compelling to some people (like Graziano, Dennett, etc.) while the musical worldview is compelling to others (Peterson, McGilchrist, etc.). If you are familiar with my work you will probably know where I am going with this.

I do not think that the difference between the mechanistic and musical worldviews is one that can be reconciled through argument, except perhaps for those who are on the fence about it. This is because the difference between these worldviews is a difference not of belief but of perception. People on either side of this divide perceive the world very differently from each other.

In short, one either perceives the world as an interconnected whole or one perceives the world as a series of relatively disconnected parts. If you do not perceive the interconnectedness of everything, I doubt that any rational argument will suddenly remove the scales from your eyes (although five dried grams of psilocybin mushrooms probably will). Arguments are not particularly important for these perceptions.

In my own research I study a continuum of individual differences referred to as the autism-schizotypy continuum. The publication that is most relevant to this discussion can be found here.

The “autistic” type of perception is relatively better at looking at the parts of the world, understanding those parts in mechanistic terms (i.e., in terms of efficient causation), and using that understanding to predict and manipulate the world so as to bring about desired outcomes. This is what I have elsewhere called the “engineering” mindset.

The “positive schizotypal” type of perception is relatively better at seeing emergent wholes and the emergent properties of those wholes. Persons are emergent wholes and people on this side of the continuum tend to be more skilled intuitive psychologists (except when they are on the verge of psychosis). This is what I have elsewhere called the “poetic or prophetic” mindset.

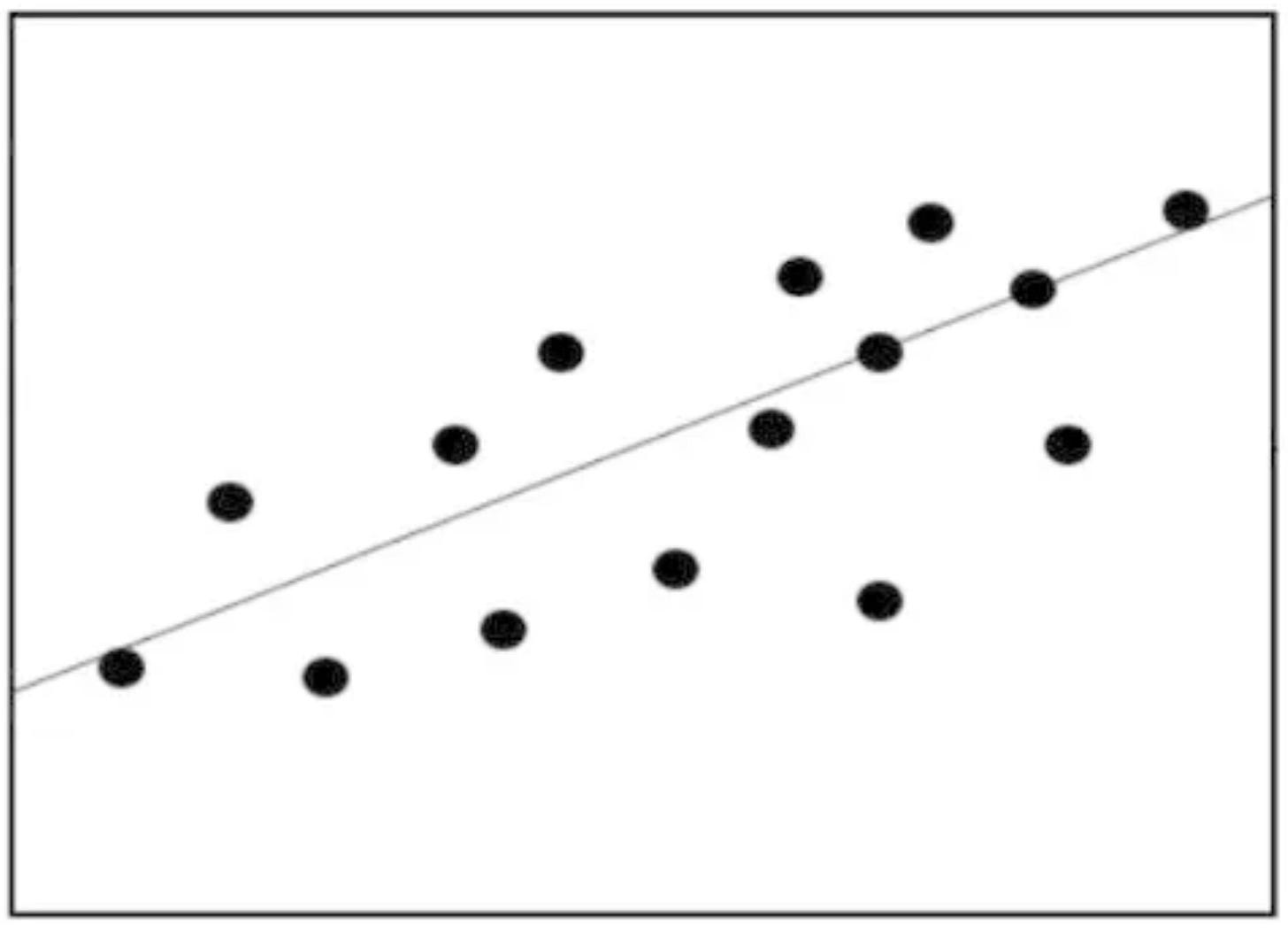

Technically, there is always a tradeoff between overfitting and underfitting a statistical model to any set of noisy data, which includes sensory data. This tradeoff is demonstrated in the images below.

The top image show that people high in positive schizotypy underfit when dealing with complex but low-noise data (e.g., computer programming languages and other rules-based systems).

The bottom image shows that people high in autistic-like traits overfit when dealing with noisy data (e.g., the behavior of other human beings, historical patterns).

Here is a hypothesis: When you look at the world up close, in detail, this is basically what you should see:

However, when you zoom out and look at the world as a whole, especially across vast spans of time, this is what you should see:

Obviously these are simplistic representations, but hopefully you get my point. The world close up is precise and detailed, even if complex, but in order to get a sense of the whole (especially as that whole manifests across long spans of time) one must be able to ignore irrelevant details.

This perceptual difference is represented in fiction as the difference between the Architect and the Oracle in The Matrix movies. The Architect describes his creation as “a harmony of mathematical precision” but suggests that there are “aspects of the human psyche” that he is unable to understand. Understanding these aspects will require a mind that is “less bound by the parameters of perfection”, i.e., one that is less precise; the Oracle.

Precision is a tradeoff. Those who have precise minds are very good at dealing with precise systems and are not so good at dealing with imprecise ones. Those with relatively imprecise minds (like myself) have the opposite skillset.

A problem occurs when people have a perceptual style that is ill-fitted to their task. The “engineering” mindset (as represented by the Architect) is very good at dealing with precise, rules-base systems. The problem is that the world, as a whole, is not best understood as a precise, rules-based system. Understanding the world as a whole, including its patterns of transformation across time, will require ignoring (or treating as unimportant) many details in order to avoid overfitting. This means, in my opinion, that while the engineering mindset may be very good at understanding, predicting, and controlling parts of the world, it is not so good at understanding the world as a whole because it overfits its models.

The “poetic or prophetic” mindset (as represented by the Oracle) is proficient at understanding noisy patterns as opposed to rules-based patterns. The world as a whole (including its transformations across vast spans of time) is best understood as a noisy pattern. This means that people with the poetic or prophetic mindset are relatively better at understanding the world as a whole even if they are not as good at tasks that require an “engineering” mindset (e.g., mastering precise, rules-based systems). Of course, there is another problem that can occur on this side of the continuum, which is underfitting their models to the world. This can manifest in a number of ways (e.g., hyper-conspiratorial worldviews or worldviews that are too vague to be useful). Nevertheless, it is only by risking underfitting that one can ever pick up on noisy patterns that actually exist. It’s a necessary tradeoff.

The meaning of the world is to be found in the whole and not in the parts, just as the meaning of music can only be found in the whole and not in the parts. This is why, for those on the “engineering” side of the continuum, meaning can seem like some overly vague or woo-woo concept (since they can’t ‘see’ it) while to those on the “poetic or prophetic” side of the continuum, meaning is so obviously real and fundamental. The perception of meaning is dependent on the perception of integrated wholes rather than disconnected parts. Those who are less able to see integrated wholes are also less likely to see and understand meaning.

This is not an argument that I am making. I see the musicality of the world in the same way that I see that the sky is blue (and almost as clearly). I see the world as an interconnected whole, in which every aspect of the world (life and death, suffering and pleasure, strength and weakness, health and sickness, good and evil, etc.) has its necessary place in the overall pattern of transformation and complexification. My perception of the musicality of the world is something that I have earned through many thousands of hours of obsessive reading and exploration. Of course, perceiving the musicality of the world means that we will need to rethink the idea that efficient causation is sufficient to explain the world, but that is a discussion for another time.

For those who don’t see it, I’m not sure there is any way to convince them through some presentation of argument or evidence. I seriously doubt, for example, that Michael Graziano will ever be able to see the musicality of the world even if he is somehow able to accept it intellectually. Some people lack the perceptual equipment to see it, just as I lack the perceptual equipment which would have allowed me to ever have become a great chemist or engineer.1

Let us assume for a moment that the world is like music. Then we could slightly change the quote from Nietzsche above to say:

Assuming that one estimated the value of [the world] according to how much of it could be counted, calculated, and expressed in formulas: how absurd would such a “scientific” estimation of [the world] be! What would one have comprehended, understood, grasped of it? Nothing, really…

The mechanistic worldview has comprehended, understood, and grasped nothing of the world as it is, even if it has allowed us to predict and control parts of it. This mistake — of assuming that a model which allows us to predict and control parts must also be applied to the world as a whole — is one aspect of the meaning crisis.

The world is far more mysterious than that.

Graziano is an easy punching bag here. To be clear, I know nothing about him personally and have nothing against him as an individual. He’s just the most obvious example of the most extreme version of a mechanistic worldview.

Throughout literature and philosophy, one commonly sees this tension between the mechanistic worldview and the musical one, like you said. They are really two differing archetypes, two modes of thought each producing their own way of interpreting the world.

I’m reminded of what theologian Sergei Bulgakov wrote, “for the enlightened eye of the saints, the world is a continuously-enacted miracle but conformity to mechanical law of the world […] conceals divine Providence from us.”

Philosopher Hannah Arendt put it more secularly, “the new always happens against the overwhelming odds of statistical laws and their probability. The new therefore always appears in the guise of a miracle.”

I've always been drawn to this view. Grasping life and history mechanically is to not really grasp it at all. Additionally, I think the day history and life moves entirely by mechanical laws and predictive power, is the day humanity ceases to exist - luckily, life has not yet been reduced to inputs and output

When is the next installment to the YouTube series!