Nietzsche’s Wager > Pascal’s Wager

The Eternal Return in Contrast to Pascal’s Wager

There has been some debate around Substack lately about Pascal’s wager. For those not in the know, Pascal’s wager basically says that even if the odds of God being real are 1/100,000,000,000 (or whatever), that you should still believe in God because the expected value of believing in God outweighs the expected value of not believing in God. This is because there is a non-zero chance that your eternal soul will go to heaven or hell based on your belief or non-belief in God. You can read Bentham's Bulldog’s explainer here.

When I read this kind of argument I always end up thinking to myself that even if it were true, I still wouldn’t give a shit. Its truth or falsity is simply irrelevant to me. The people making this kind of argument, and the people who find it compelling, might as well be a different species.

It’s not that there is anything unreasonable about Pascal’s wager. The potential cost of believing in God seems to be very small. You could be wrong about God’s existence, and if so then little is lost. The potential cost of not believing in God seems to be very high. You could be wrong about God’s non-existence, and if so then your eternal soul will miss out on an eternity of smoking doobies in heaven with the big guy, or something like that (and instead, you will be smoked by the devil forever and ever). So there are very asymmetric costs to believing and not believing. Believing costs almost nothing, while not believing potentially costs you an eternity of torment or bliss.

This is a good argument! It’s reasonable! The math checks out! And yet… I just don’t care. Not even a little bit. I think if you were to prove to me beyond all reasonable doubt that this kind of God exists, I would be even less likely to believe in him out of sheer spite.

On this Substack I have made a case for the existence of God, but not that kind of God. The kind of God I made the case for is not a cosmic daddy who doles out good boy points (to be redeemed at a later date) for believing in him, and eternally torments you if you don’t. If that kind of God actually existed, I’d be on team Satan for sure. I’d be playing AC/DC all the way to an eternity of torment in the lake of fire.

Maybe this comes across as me just being an edgelord, but it’s true! Perhaps if you were to prove to me that such a God exists, I would capitulate to him out of fear of his eternal carrot-and-stick, but I would still be secretly thinking to myself that the devil was probably right to stage a rebellion. Richard Hanania is right to call Pascal’s wager (and the view of God it depends on) a form of “spiritual extortion” because that’s exactly what it is. Any God who needs to extort everyone with threats and rewards in order to gain their obedience is a God that is worthy of being rebelled against.

Faithful to the Earth

It’s a good thing, then, that we have no good reason to believe such a God exists, or that the fate of our soul rests on such beliefs, or that there is any such thing as an eternal disembodied soul to begin with. For us post-Nietzscheans, that God is dead. And good riddance.

I beseech you, my brothers, remain faithful to the earth, and do not believe those who speak to you of otherworldly hopes! Poison-mixers are they, whether they know it or not. Despisers of life are they, decaying and poisoned themselves, of whom the earth is weary: so let them go.

Once the sin against God was the greatest sin; but God died, and these sinners died with him. To sin against the earth is now the most dreadful thing, and to esteem the entrails of the unknowable higher than the meaning of the earth. (Nietzsche, Zarathustra Prologue 3)

The most dreadful thing is to sin against the earth by valuing the unknowable more than the meaning of the earth. What does that mean? It means that positing the existence of an unknowable, unseeable world—which is supposedly more important than the only world that actually exists—is a kind of pathology, and we should be done with it.

The invention of heaven and hell (and all other afterlife scenarios) is the result of an imagination that is displeased with the world as we see it. These imaginary scenarios come from a kind of person who is displeased with the suffering, injustice, and impermanence of this world, and would like to imagine their way out of it.

They desire that there should be some other world, which would be more pleasing, in which there will be no more suffering (at least for them), no more injustice, and no more passing away. In this other world, our enemies will be tormented by the devil forever and ever, while we true believers will be given an eternity of happiness with God. How cool would that be!?

But this explains everything. Who alone has good reason to lie his way out of reality? He who suffers from it. But to suffer from reality is to be a piece of reality that has come to grief. The preponderance of feelings of displeasure over feelings of pleasure is the cause of this fictitious morality and religion; but such a preponderance provides the very formula for decadence. (Nietzsche, Antichrist 15)

These imaginary scenarios were created by certain neurotic people who could not find justice in this world, and so invented a world where cosmic justice reigns (ahem, Paul). They lie their way out of reality because they suffer from reality. We, on the other hand, are not so neurotic as to require palliative lies. We will remain faithful to the earth.

Nietzsche’s Wager

What about those of us who have no need for imaginary afterlife scenarios? We are not concerned with the fate of our eternal soul, but with how to live here and now, in this body, on this earth. For us, Nietzsche poses a different kind of wager:

What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: “This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unutterably small or great in your life will have to return to you, all in the same succession and sequence—even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned upside down again and again, and you with it, speck of dust!”

Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: “You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.” (Nietzsche, The Gay Science 341)

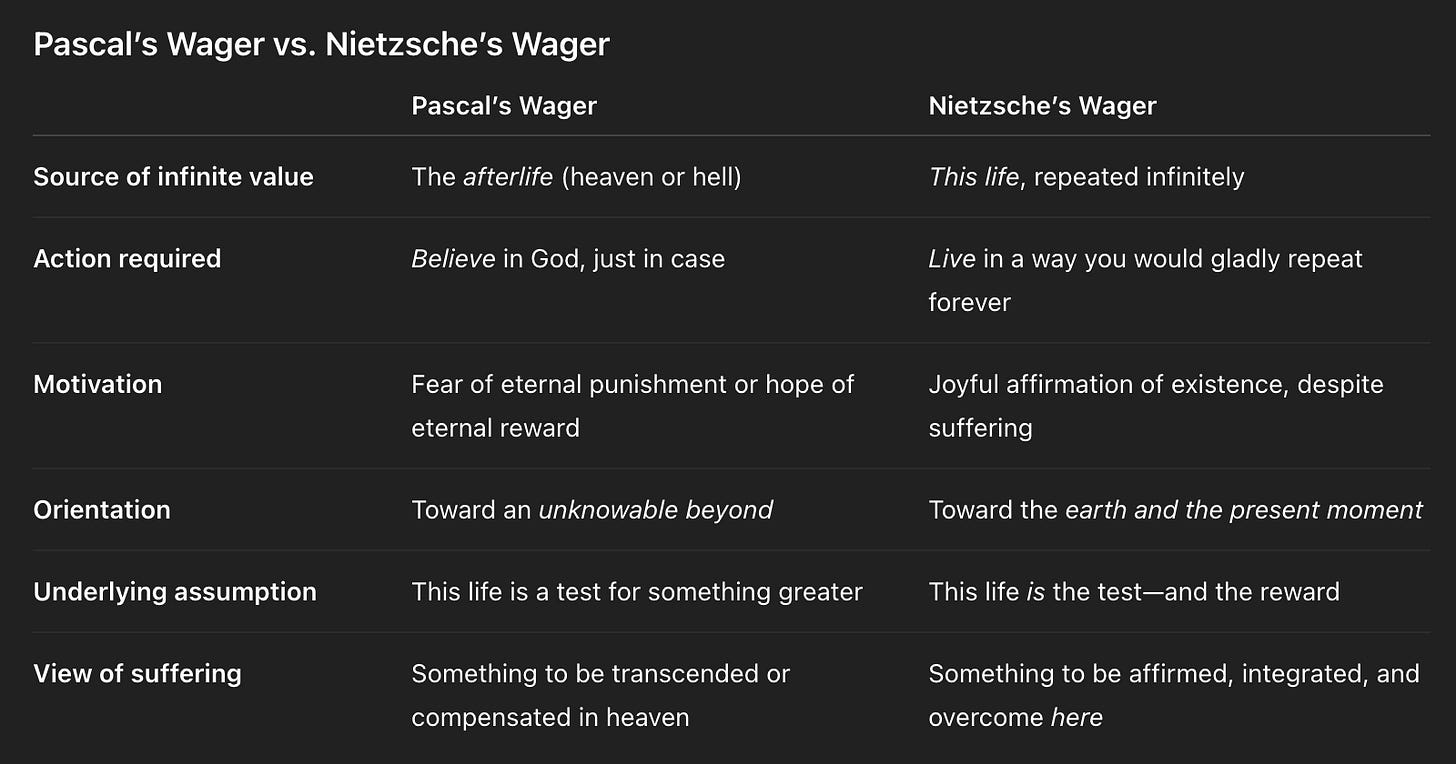

This is the eternal return of the same. Nietzsche asks us how we would respond if we were informed that we would have to live this life, exactly as it is, over and over again for all eternity. As a thought experiment, this is nearly the inverse of Pascal’s wager. Pascal’s wager assumes that your life on earth is finite, and that your afterlife is infinite. Nietzsche’s wager assumes something like the opposite of that—what if your afterlife is non-existent, and your life here on earth will be experienced infinitely? You should live in such a way that this fact would be experienced as a gift rather than a curse. This means that the goal for life is no longer located outside of life, but within life itself. Below is a table comparing the two wagers:

My sense is that Nietzsche is not presenting the eternal return as a scientific hypothesis (though he did play with the idea of explaining it scientifically), but as a method for evaluating your own life. Would the eternal return be heaven, or hell for you? Could you live in such a way that you would desire the eternal return of the same?

But let’s be clear. Nietzsche didn’t think the thought of eternal return would be good for everyone. In fact, he thought that most people would necessarily see it as a curse. It is difficult to live in such a way as for the eternal return to appear as a blessing. It is not for the many, but for the few. This is also in sharp contrast to Pascal’s wager. Anyone can believe! It’s easy! Pascal’s wager is something that almost anyone could capitulate to, at least in principle.

But could anything that easy, and that common, be worth attaining?

—

Go check out the Nietzsche Podcast video on this topic, which was a useful resource for writing this post:

Hi Brett, I agree with you about Pascal's wager being spiritual extortion. Do you think Nietzsche himself lived up to his wager, though? He spent the last decade of his life bedridden and insane, allegedly had syphilis, never married (the woman he proposed to rejected him multiple times, and he kept pining for her), no children, posthumous fame, etc. Emil Cioran, who was compared with Nietzsche, said this about him: “What I consider his most authentic work is his letters, because in them he’s truthful, while in his other work he’s prisoner to his vision. In his letters one sees that he’s just a poor guy, that he’s ill, exactly the opposite of everything he claimed….It’s because that whole vision, of the will to power and all that, he imposed that grandiose vision on himself because he was a pitiful invalid. Its whole basis was false, nonexistent. His work is an unspeakable megalomania. When one reads the letters he wrote at the same time, one sees that he’s pathetic, it’s very touching, like a character out of Chekhov. I was attached to him in my youth, but not after. He’s a great writer, though, a great stylist.” And Carl Jung stated that Nietzsche delved into the unconscious without knowing what he was doing, and he was destroyed by what he encountered there - in Memories, Dreams, Reflections he looked at Nietzsche as a cautionary tale.

I would be interested in why you find him to be the end-all-be-all; you have structured all your writings around him. What is it about him that so deeply speaks to you? Personally I find his transvaluation of values arguments in his Genealogy of Morality to be brilliant - tracing Christianity back to Judaism, basically, but a lot of the other stuff doesn't quite hit with me. For me, Jung's perspective resonates more deeply, because he strives for *wholeness* as an end goal rather than ecstatic ruin, and we see this in his life - his marriage, having five children, having a successful clinical practice, his great body of work, etc. - he pulled off the kind of life that I myself aspire to, something actually worthy of "Nietzsche's wager" - he shows what it looks like to live the wager, to carry the burden of the unconscious without disintegration...In other words, if Nietzsche’s wager reveals the abyss, Jung shows what it might mean to survive it.

Excellent. To me, anyway. If I may, perhaps ironically or mischievously, use the words of Jesus here, "He who has ears, let him hear."