Decoding Jordan Peterson's Maps of Meaning, Part 2

The eternal categories of experience are revealed by the scientific study of psychedelics

*Note: See here for part 1

The experiential domains we inhabit… are… permanently characterized by the fact of the predictable and controllable, in paradoxical juxtaposition with the unpredictable and uncontrollable. The universe is composed of “order” and “chaos” – at least from the metaphorical perspective. Oddly enough, however, it is to this “metaphorical” universe that our nervous system appears to have adapted. (MoM p. 31)

In the above quotation, Jordan Peterson suggests that we are neurologically adapted to the “metaphorical” universe of order and chaos. I suspect, however, that the word “metaphorical” is not doing justice to the reality of our situation. We are adapted to the universe as it actually is, and the universe as it actually is just is made out of order and chaos, insofar as we properly understand what is meant by these terms. Although this essay will focus on these categories in psychological terms, a future essay in this series will reveal their ontological basis as well.

In its popular conception, chaos has a negative connotation. Chaos is thought of as something that we should avoid. This is definitely not how Jordan Peterson is using the term. Order and chaos are not opposites, with one being good and the other bad. They are, instead, two sides of the same coin, mutually necessary and co-constituting. Order breeds chaos and vice-versa.

Order is not better than chaos or vice-versa. Order is necessary, but too much order is oppressive, boring, and stagnant. Chaos is both destructive and creative. Some destruction is necessary for anything truly novel or creative to emerge (as was pointed out by Nietzsche many years earlier). Chaos therefore represents both a threat and an opportunity. It is the revitalizing force and the birthplace of everything new.

The Eternal Categories of Experience

Near the beginning of MoM, Jordan Peterson describes the three major categories of experience. These categories characterize the experience of all conscious cognitive agents, from the most simple to the most complex. These are:

Explored territory (order)

The process of exploration (which occurs at the border between order and chaos)

Unexplored territory (chaos)

Explored territory does not necessarily refer to physical territory, but rather to the experience that occurs when I am engaged in a familiar task and everything is going according to plan. When I am driving to school, on the same route I have taken hundreds of times before, I do not feel any anxiety or uncertainty in relation to my task. My heart rate is stable. Adrenaline is not flowing through my veins. I’m just going through the motions, like I did last week and the week before. During drives like this I am mostly unconscious of what I am doing, relying on force of habit to guide me to my destination. My drive from home to school is therefore explored territory. My experience of it is characterized by emotional stability and a mild sense of boredom. This is the basic structure of a normal experience.

Under normal circumstances I have a conception of the way the world is and a conception of the way the world ought to be (i.e., “what is” and “what should be”). Sometimes I am consciously aware of these conceptions but that need not be the case. I also have a planned sequence of behavior designed to move me from “what is” to “what should be”. In the example above, my conception of “what is” consists of the fact that I have class today and I’m currently at my apartment. My conception of “what should be” is that I need to be at the university so I can go to class. My planned sequence of behavior is to get in my car and drive to campus (along with all of the sub-routines associated with that). The figure below represents this very normal structure of experience.

Sometimes, however, this normalcy can be interrupted. When my plans are interrupted, I may find myself in unexplored territory (i.e., chaos). For example, one day on my way to school I happen to look at my schedule and realize that I have forgotten about an important meeting today — one which may determine whether I have a future career in academia. The meeting is in two minutes and I’m going to be late. My anxiety goes through the roof. My mind begins to race as I think of ways I could get to campus faster than usual. I begin to think of the excuses I might use to explain my tardiness. I begin to think of my future life as a broke adjunct as all my hopes and dreams go out the window, etc., etc. In this case, “normal life” has broken down and psychological chaos has ensued. Although I am still in the same physical place, my experiential location has shifted. I am now in unexplored territory.

Unexpected events can also, of course, have a positive connotation. If an attractive person begins flirting with you, this can (if unexpected) also raise anxiety levels and lead to racing thoughts, but for a very different reason. Here also you are playing out all of the possible scenarios of what could happen in your mind, but the valence is decidedly positive. Chaos (i.e., the unexpected) need not be negative.

These are the basic categories of experience for Peterson. When things are going according to plan, emotions are stable and we remain largely unconscious of our task. When the unexpected and/or undesirable happens, we are thrown into a state of emotional turmoil. This can happen on a small scale (e.g., when you find out that a dentist appointment has been cancelled) or on a larger scale (e.g., when you find out that your spouse has been unfaithful). Small disruptions to our plans lead to smaller amounts of negative emotion. Large disruptions can lead to intense anxiety, depression, and in some cases even psychosis.

Being late for a meeting or being unexpectedly hit on by an attractive member of the opposite sex are pretty mild forms of uncertainty, all things considered. What happens when you encounter something truly novel and unexpected? What happens when you encounter something so foreign to you that you do not know whether to categorize it as positive or negative? In the case of a truly anomalous experience, you have two choices: On the one hand, you can deny the anomalous nature of the phenomenon and place it into some pre-determined category. For example, the skeptic who sees an unidentifiable object in the sky may decide that it was a weather balloon, military test, or something that is otherwise banal and uninteresting. The other option is to accept the reality of the anomaly and experience the dissolution of your previous conceptions attendant upon that acceptance. This will increase one’s anxiety in the short term and will require you to engage in a process of exploration in order to categorize the anomaly as positive, negative, or some combination of the two. This process of exploration will be necessary to determine the motivational relevance of the anomalous experience. This process consists of:

The anomalous experience that disrupts your current conceptualization of the world (i.e., your conception of where you are, where you are going, and how you are going to get there).

The dissolution of one’s previous conception of the world in response to the anomalous experience (i.e., the descent into chaos and the anxiety that accompanies that descent).

Exploration to determine the motivational significance of the anomalous experience.

Re-emergence into a new conceptualization of the world that incorporates the anomaly.

Peterson refers to this process as “revolutionary adaptation” (in contrast to “normal life”) and represents it like this:

Revolutionary adaptation consists of the disintegration of “normal life” in response to some anomalous information. This disintegration is accompanied by a descent into chaos, which tends to manifest psychologically as an increase in anxiety. Finally, there is a re-emergence into a new form of life that incorporates the anomaly and therefore represents a higher form of order.

The choice we are faced with when presented with an anomalous experience is between denying the anomalous nature of the experience and carrying on with “normal life” (thus maintaining order and stability) or accepting the anomalous nature of the experience and experiencing a descent into chaos, along with the anxiety that accompanies that descent.

Sometimes maintaining normal life is the best option. We don’t want to have to re-formulate all of our conceptions of the world every time something novel or unexpected happens. Sometimes, however, the maintenance of stability isn’t enough. If the circumstance is extreme enough, we must take the plunge into chaos in order to potentially re-emerge with a new and more functional conceptualization of the world.

In Peterson’s scheme, this process of revolutionary adaptation occurs at the border between order and chaos (we’ll talk more about what that means further below).

Psychedelic Research and the Categories of Experience

In the following sections I will argue that the recent resurgence of research on classic psychedelics (especially psilocybin) supports Jordan Peterson’s descriptions of the categories of experience. Three different theories derived from the modern study of psychedelics all point to the idea that Peterson’s categories of experience accurately reflect the underlying neurobiological reality. All three theories come from the mind of Robin Carhart-Harris (who has been at the forefront of the modern resurgence of the scientific study of psychedelics). These theories tell us that:

The serotonin receptor that psychedelics act on (5-HT2A) facilitates what Peterson calls “revolutionary adaptation” while the other most widely studied serotonin receptor (5-HT1A) facilitates what Peterson calls “normal life”.

The entropic brain theory suggests that the revolutionary adaptation mediated by psychedelics emerges at the border between order and chaos in the brain, in accordance with Peterson’s suggestion that revolutionary adaptation occurs at the border between order and chaos.

The REBUS (Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics) model of the function of psychedelics shows in more detail how psychedelics facilitate “revolutionary adaptation”, and how this follows the same pattern detailed by Peterson above (i.e., a descent into chaos followed by a re-emergence into a higher form of order).

I will describe these theories in more detail in the sections below.

Normal Life, Revolutionary Adaptation, and the Serotonergic System

Serotonin, also known as 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), is a neurotransmitter, the function of which is somewhat mysterious if only because it is so apparently complex. There are a variety of 5-HT receptors in the brain. The two most well-studied are called 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A. The classic psychedelic drugs (e.g., psilocybin, LSD, mescaline) are all 5-HT2A agonists, meaning that they bond to 5-HT2A receptors. The most commonly prescribed anti-depressant drugs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors; SSRIs) are hypothesized to work primarily on the 5-HT1A pathway, enhancing the function of these receptors.

Robin Carhart-Harris, who has carried out much of the recent research on the effects of the classic psychedelic psilocybin, has put forward a novel theory (with his co-author David Nutt) on the functions of serotonin in light of these facts about the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors. As we will see, their theory has substantial overlap with Jordan Peterson’s characterization of the structure of experience as described above.

In their 2017 paper entitled “Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors”, Carhart-Harris and Nutt posit that the 5-HT1A receptor and the 5-HT2A receptor have diametrically opposed functions in the brain. The 5-HT1A receptor works to facilitate what they refer to as passive coping while the 5-HT2A receptor works to facilitate active coping. These different kinds of coping are optimal in different kinds of situations. As Carhart-Harris and Nutt put it:

We suggest that the 5-HT1AR and its associated functions dominate 5-HT transmission under normal conditions but that 5-HT2AR signalling also serves a role that becomes increasingly important during extreme states when 5-HT release is elevated. (p. 1092)

This paper… proposes that the principal function of brain serotonin is to enhance adaptive responses to adverse conditions via two distinct pathways: (1) a passive coping pathway which improves stress tolerability; and (2) an active coping pathway associated with heightened plasticity, which, with support, can improve an organism’s ability to identify and overcome source(s) of stress by changing outlook and/or behaviour. Crucially, we propose that these two functions are mediated by signalling at postsynaptic 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors respectively, with 5-HT1AR signalling dominating under ordinary conditions but 5-HT2AR signalling becoming increasingly operative as the level of adversity reaches a critical point. (p. 1107)

Under “normal conditions”, passive coping mediated by 5-HT1A dominates. During “extreme states”, active coping mediated by 5-HT2A becomes more important. This reflects the fact that under normal circumstances, we should usually stay on our current course rather than radically change our behavior or outlook. Post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptor signalling appears to mediate this type of behavior. In more extreme circumstances, we should be more willing to radically change our behavior and outlook. 5-HT2A receptor signalling appears to mediate this type of behavior.

There are multiple lines of evidence that Carhart-Harris and Nutt bring to bear on their hypothesis, but here I will focus on their review of the effect of two classes of drugs: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and classic psychedelics (e.g., psilocybin, LSD, mescaline). Interestingly, SSRIs and classic psychedelics have both been used for the treatment of depression, but their mechanism of action is quite different. SSRIs are thought to function by increasing 5-HT1A receptor sensitivity levels, thus working through pathway 1 (i.e., passive coping, stress tolerance). Classic psychedelics are 5-HT2A agonists, meaning that they work through pathway 2 (i.e., active coping, increased plasticity).

The effects of these drugs provide evidence that SSRIs are associated with passive coping and psychedelics with active coping. For example, one common side effect of SSRIs is “emotional blunting”, thought to effect between 40-60% of people who take these drugs. There is some debate about this, with some studies suggesting that emotional blunting is not caused by SSRIs but is rather a residual effect of the depression that the SSRIs are meant to treat. The preponderance of evidence, however, suggests that SSRIs are causing emotional blunting that cannot be attributed to the pre-existing condition of depression. For example, many patients report that the emotional blunting recedes after they stop taking the medication.

Lethargy (i.e., lack of energy and enthusiasm) is another common side effect of SSRIs. Both lethargy and emotional blunting can be plausibly considered a manifestation of “passive coping” in that they reduce one’s reactivity in the face of adverse circumstances (i.e., by not reacting emotionally and/or by failing to react at all). Both of these side effects are consistent with Carhart-Harris and Nutt’s thesis that post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors facilitate passive coping.

Under extreme circumstances, passive coping is not enough. We must be willing to radically alter our behaviors, beliefs, and goals. In this case, 5-HT2A receptors appear to play the dominant role. The effects of classic psychedelic drugs, being 5-HT2A agonists, provide some evidence for this role of 5-HT2A in active coping. Psychedelic drugs are associated with the experience of insight (which necessarily precedes a radical change in behavior), increased susceptibility to environmental influences (i.e., the effects of set and setting on a psychedelic trip), and long-term changes in behavior and personality.

This latter finding was very surprising to many psychologists. Psychology has a long history of trying to induce long-term (hopefully positive) changes to people’s personality and cognition through short-term interventions. This history is almost entirely one of failure. People’s long-term behavior just doesn’t respond to the kinds of interventions psychologists use to affect it. Psychedelic drugs seem to be an exception to this.

For example, people who had a “mystical experience” under the influence of psilocybin were shown to have an increase in the personality trait of “openness to experience” up to a year after administration of a single dose. Another study found that people who took a high dose of psilocybin showed positive changes in interpersonal closeness, gratitude, life meaning/purpose, forgiveness, death transcendence, and daily spiritual experiences that persisted for at least 6 months after the initial dose. Psilocybin has also been used successfully for smoking cessation, with 60% of participants remaining abstinent after a long-term (>16 months) follow up.

Some of these findings have small sample sizes and should be subjected to replication. Nevertheless, the preponderance of evidence strongly suggests that psilocybin has the potential to cause long-term changes to behavior and personality. These findings tell us something about the role of 5-HT2A receptors. Unlike post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors (which seem to induce emotional blunting and lethargy as mechanisms for passively coping with stressors), 5-HT2A receptors induce active coping, leading people to make long-term changes to their behavior and personality.

Unlike the emotional blunting caused by SSRIs, psychedelic experiences can be highly emotional, with people sometimes crying profusely, laughing hysterically, and/or experiencing extreme fear and anxiety during the trip. The subjective experience during the trip is not unrelated to its long-term effects. Some long-term effects depend on whether people report having had a “mystical experience”, for example. Psychedelics therefore seem to facilitate the category of experience that Peterson calls “revolutionary adaptation”.

Order, Chaos, and the Entropic Brain

In MoM, Peterson suggests that the process characterized by revolutionary adaptation occurs at the border between order and chaos. Given the evidence reviewed in the previous section that psychedelics can facilitate this kind of adaptation, it is remarkable to note that psychedelics have been hypothesized to function by moving the brain closer to the border between order and chaos. In their 2014 paper “The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs”, Carhart-Harris and colleagues argue that psychedelic drugs work by increasing entropy in the brain, moving us closer to a state of “criticality”. I discussed this idea in some detail in a previous post, but I will briefly review it again here.

Self-organized criticality is a term that refers to the tendency of complex dynamical systems to self-organize (from the bottom up, without any tuning from an outside agent) to the narrow window between order and chaos. This term was originally introduced by Per Bak, a physicist attempting to understand the emergence of complexity in nature. Criticality has since become an important concept in biology because of theoretical arguments suggesting that biological systems function optimally at the border between order and chaos in addition to empirical evidence suggesting that systems such as genetic regulatory networks, flocks of birds, and the brain exhibit signatures of criticality.

The relation between brain functioning and self-organized criticality has gained increasing recognition over the last ten years. In particular, there is some important connection between criticality and consciousness (I review that evidence in some detail here). Given the connection between criticality and consciousness, it is not too surprising that psychedelics are hypothesized to move people closer to criticality, given that these drugs are sometimes described as “expanding” or intensifying one’s conscious experience.

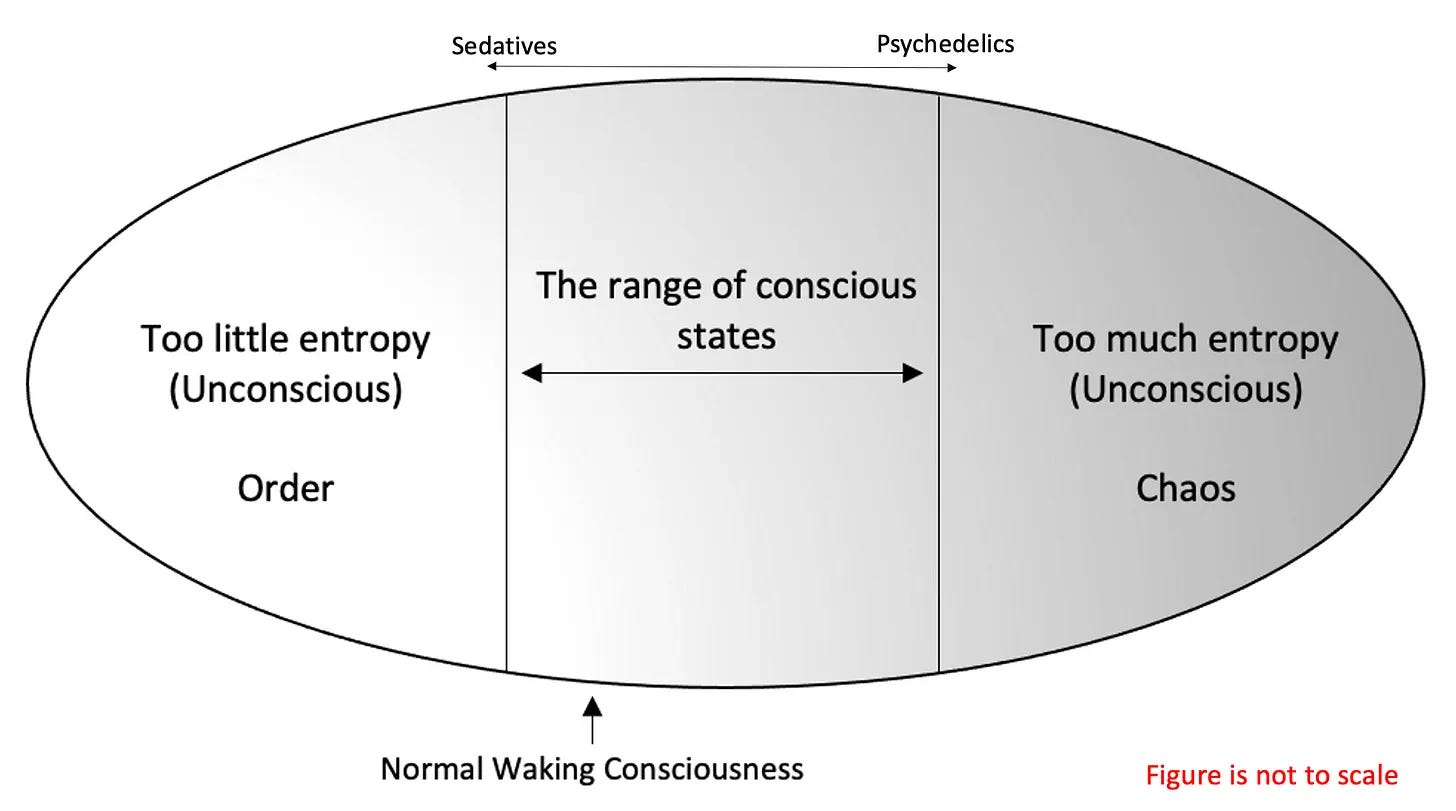

The figure below represents a summary of the entropic brain theory.

Consciousness emerges at the border between order (too little entropy) and chaos (too much entropy). During normal waking consciousness, however, most people are slightly tilted towards order. According to Carhart-Harris and colleagues, this tilt towards order allows people to represent the world more precisely in order to exert more control over the world. However, it can also make them more rigid in their behaviors and conceptions. Psychedelics increase entropy in the brain, moving people closer to true criticality. This move towards criticality can facilitate insight, allowing for deep-seated patterns of thought and behavior to change. This is equivalent to the process of revolutionary adaptation. Carhart-Harris and Friston’s (2017) REBUS model of psychedelics provides a framework for understanding how psychedelics can facilitate this kind of revolutionary change.

The Structure of Insight and the REBUS Model of Psychedelics

Robin Carhart-Harris’ and Karl Friston’s 2019 REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics) model can shed some light on how it is that psychedelics drugs facilitate long-term changes to people’s behavior and personality. For the purposes of this essay I am going to simplify the theory a bit, but if you want the full story the paper is freely available online.

We can think of the mind as consisting of a nested hierarchy of goals and beliefs (both of which are construed as ‘predictions’ within the predictive processing framework that the REBUS model is based on). The hierarchy can be thought of in terms of levels of generalization, with more general and long-term goals/beliefs near the top of the hierarchy and more specific and short-term ones near the bottom.

In a previous paper of mine I argued that the top of the hierarchy contains predictions related to what Ann Taves and colleagues (2018) refer to as a worldview. These are questions like “what exists?”, “how do I know what’s true?”, and “what is good and bad?”, asked in the most general possible sense (see my paper here). In humans, the answers to these questions often take the form of religious or metaphysical claims. As Carhart-Harris and colleagues point out, the higher levels of the hierarchy will also contain implicit beliefs related to the self or ego.

Under normal circumstances, our experiences in the world only affect goals/beliefs at relatively low levels of the hierarchy. Under normal circumstances, that is, we do not change our entire worldview and self-concept as a result of sensory experiences. These things only change under extreme circumstances (which Peterson refers to as “revolutionary adaptation”).

When we change high-level beliefs like this, we experience this change as an insight or an ‘aha’ moment. The time period preceding the insight can be accompanied by anxiety or other kinds of psychological turmoil depending on the level of the hierarchy at which the insight is taking place. Some insights reflect changes to relatively low-level beliefs and this would correspond to our normal (relatively anxiety-free) experience of an insight. If, however, we have an insight about the highest levels, this may be accompanied by some emotional turmoil. When we have insights like this at the highest levels of the hierarchy, we will tend to perceive them as a religious conversion or a mystical experience. For example, when a long-time alcoholic experiences a religious conversion and changes his life, he often experiences this as a sudden insight.

By increasing entropy in the brain, psychedelics allow the higher levels of the hierarchy to change more easily. In other words, psychedelics facilitate high-level insights, which is why their use can facilitate mystical experiences and long-term changes to behavior. In order to understand how this works, I must briefly review some cognitive scientific research on the structure of an insight.

In a 2009 paper entitled “The Self-Organization of Insight: Entropy and Power Laws in Problem Solving”, cognitive scientists Damian Stephen and James Dixon put forward an understanding of the structure of an insight from the point of view of dynamical systems theory. I reviewed this literature in more detail in a previous post (which you can read here), so in this post I will just extract two key points. Stephen and Dixon provide evidence that:

Insights are a self-organized critical phenomenon, meaning that they emerge at the border between order and chaos.

Insights involve a process in which there is a temporary increase in entropy followed by a decrease in entropy such that there is even less entropy than before (in psychological terms, entropy can be thought of as uncertainty).

The structure of an insight according to Stephen and Dixon can be summed up by the figure below:

In this process, people start out with a relatively stable way that they are framing the world (corresponding to the flat level of entropy at the left side of the figure). They then break that frame, causing an increase in entropy (corresponding to the trough that occurs after breaking frame). They then adopt a new frame that decreases entropy such that there is even less entropy than before (the new and higher flat line on the right side of the figure).

Compare this process with the process of revolutionary adaptation characterized by Peterson in MoM (with the figure near the beginning of this essay labelled as “Figure 4”). In Peterson’s representation, there is an initial state of “order” corresponding to our enactment of what he calls a “story”. Peterson’s “story” is functionally equivalent to what the cognitive scientists call a frame. An anomaly occurs which disrupts that story, causing a “descent into chaos”. This is equivalent to the increase in entropy that occurs after breaking frame in the figure above. Finally, a new story is established which corresponds to a higher form of order. It’s a higher form of order because it takes into account everything that the previous story did and it takes into account the anomaly that disrupted the previous story. This higher form of order is equivalent to the new frame that is established as a result of the insight, which facilitates a decrease in entropy such that there is even less entropy than before.

The psychological manifestation of entropy is uncertainty. More entropy = more uncertainty. By increasing entropy in the brain, psychedelics decrease our certainty about our high-level beliefs and goals, thus allowing us to have insights in which they can change. This increase in uncertainty corresponds to what Carhart-Harris and Friston (2019) refer to as a “relaxation of precision” on “high-level priors”. In their own words:

… we maintain that the relaxation of precision on the high hierarchical levels has the most dramatic psychological consequences[…] The principle is that the influence of the high levels runs deep, such that affecting them has particularly large or general implications. (p. 325)

The ideal result of the process of belief relaxation and revision is a recalibration of the relevant beliefs so that they may better align or harmonize with other levels of the system and with bottom-up information[…] Such functional harmony or realignment may look like a system better able to guide thought and behavior in an open, unguarded way… (p. 321)

In other words, psychedelics decrease confidence in our high-level beliefs, allowing them to be reconfigured into something that is (hopefully) more functional.

In sum, psychedelics work by increasing entropy (i.e., neural chaos) in the brain, moving the brain closer to criticality, which is the border between order and chaos. At this border, insights occur that disrupt high levels of the hierarchy of goals/beliefs, allowing high-level goals/beliefs to change in (hopefully) a functional way. In this way, psychedelics facilitate long-term behavioral changes. In other words, they facilitate what Peterson calls “revolutionary adaptation” and the process by which they do so is remarkably similar to the way Peterson characterized the process in MoM (which was written long before this research on psychedelics was available). The table below summarizes the overlap between Peterson’s “revolutionary adaptation” and the action of psychedelics as informed by the research of Carhart-Harris and others.

Conclusion

Why has Robin Carhart-Harris seemingly re-discovered some of Peterson’s ideas in his own work on psychedelics? One obvious answer is that Maps of Meaning is an intensely psychedelic book, in the literal sense of the word (the literal meaning of psychedelic is “mind revealing”). That the patterns relayed in MoM would be re-discovered in the study of psychedelics just isn’t that surprising, given the potential of these compounds for revealing the structure and dynamics of the mind.

It is also possible that the convergence between Peterson and Carhart-Harris is partially a reflection of their shared background in the psycho-analytic tradition. Both of them have been influenced by Freud and Jung (Peterson more by Jung, Carhart-Harris more by Freud).

Nevertheless, the independent discovery of the same patterns from a very different empirical basis (since Peterson doesn’t refer to psychedelics in MoM) is evidence for the plausibility of these patterns. If a pattern can be found at multiple levels of analysis using multiple methodologies, it is very likely to be real and important.

In the next essay we will look at how these categories manifest in mythological narratives. I will put forward a hypothesis about the function of mythological narratives in light of this information.

Thanks, that was a good conceptual dive.

Just loose associating here, but another variant of this idea is McAdams’ narrative theory, in which a crisis point in a person’s life induces fresh disorder, and can bifurcate along two potential paths toward a new order, the one being a “contaminated” narrative (a more negative story, like “I’m a failure because of what happened), the other being “redemptive” (a more positive story, as in “I’ve learned important things and grown as a person because of what happened”).

More broadly, chaos theory would be another way of reframing it conceptually.

Fantastic. Ego dissolution is also a huge factor, as the ego seems to act as a gatekeeper for noise. Or in other words it "orders" incoming data through it's own structure, hindering the ascent to criticality or mitigating how much the overall frame is broken by an insight. I wonder if there is a relationship between ego-attachment and propensity for insight in the scientific literarure.

Thanks and look forward to the integration with myths.